Book Review: The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers can Teach us about Success. Kevin Dutton (Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012)

Reviewed by Bob Buddemeier

Dr. Kevin Dutton is a research fellow at the Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford. He is an affiliated member of the Royal Society of Medicine and of the Society for the Scientific Study of Psychopathy, and a best-selling author.

A word about a word — “wisdom” in the title is a bit misleading, implying as it does some integration of knowledge and understanding, whereas psychopaths are defined largely in terms of hard-wired negatives (lack of empathy, remorse, responsibility). The thesis of the book, however, is that under some circumstances aspects of the hard-wired system can produce outcomes superior to those resulting from the actions — and especially the mental decision-making — of “normal” people.

This is hard to discuss with available terminology. “Psychopath” has become generally identified with the more explicit “criminal psychopath” to the point where it is difficult to communicate about benefits or good qualities associated with psychopathy. Fallon (The Psychopath Inside) uses the term “pro-social psychopath,” but that still leaves much to be desired.

In addition – another word about another word – “psychopathy” is not recognized as an accepted diagnostic term in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM includes psychopathy within its definition of Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), which Dutton alludes to as one of “the empirical and diagnostic combat zones of clinical definition.”

It’s both a strength and a weakness of Dutton’s book that he comes close to bridging the terminology gap — but doesn’t quite make it. He introduces us to the basic models and conclusions in the first few chapters, with the following sections presenting examples, details, alternatives or explanations. He makes the point that there are a number of characteristics that go into the making of a total psychopath, and that any or even all of these may be present to some degree in non-psychopaths. It’s just when all of the switches are “on,” all of the knobs are full clockwise, and all of the sliders are fully to the right that the dashboard is set for Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy. Ultimately, however, he never gets us to the Rosetta Stone that somehow couples the four psychopathic “factors” (his fig. 2.6) with the four Myers-Briggs personality types. It’s probably just as well.

Probability of Success

A moderate mixture, with only a few strong characteristics, can be very advantageous. Figure 1 is a conceptualized plot of probability of career success — whether as a criminal or a law-abiding citizen — as a function of relative psychopathy. Psychopaths are unusually sensitive to the vulnerability of potential victims; in law enforcement, an intuition for guilty behavior is a parallel. Con men and violent criminals are bad; if they are on our side, the rather similar spies and Special Forces Commandos are good. The cold-blooded decisiveness of a deadly knife-fighter finds a parallel in the skills of an expert surgeon.

Starting from these rather undeniable parallels, Dutton moves on to a more detailed examination of psychopathy, which does not exactly flow to an integrated conclusion, but which I nonetheless found interesting, informative, and even entertaining. The author writes informally in the first person, with an evident sense of humor and a “just one of the boys” style. A lot of his professional interviews seem to take place in bars, with the occasional crude expression reminding us that this is not an academic treatise.

We learn about the PPI (Psychopathic Personality Inventory) for assessing trends in the general public, the PCL-R (Psychopathy Checklist — Revised) for forensic application in prisons and hospitals, and the B-scan (for assessing psychopathy in a business context). Even more interesting are the tests, games and experiments designed to develop and apply these various measurement tools — and some of the results. In a situation where there is a choice between sacrificing a few people and allowing a large number to die, the desirable utilitarian result is much more likely to be achieved by a psychopath than by a normal person — who is too reluctant to kill at all.

In addition to meeting some chilling (or merely disgusting) psychopaths, we get some feeling for both the “good psychopaths” and for the researchers on psychopathy, who try to use an arguably somewhat normal mind/brain to describe and understand one that is nearly outside the bounds of human recognition. All are fascinating, and the combinations especially so.

Toward the end of the book Dutton comes up, in a very understated way, with the explanation for the title: “I label the skill set the Seven Deadly Wins — seven core principles of psychopathy that, apportioned judiciously and applied with due care and attention, can help us get exactly what we want; can help us respond, rather than react, to the challenges of modern-day living; can transform our outlook from victim to victor, but without turning us into a villain:

- Ruthlessness

- Charm

- Focus

- Mental Toughness

- Fearlessness

- Mindfulness

- Action”

The key — criminal, or “bad” psychopaths may possess all of the principles, but usually cannot avoid villainhood because they lack the willingness, or perhaps the ability, to apportion judiciously and appl[y] with due care and attention.

The Seven Deadly Wins can enhance most capabilities, but the outcome depends on the accompaniments – add compassion, humility, and faithfulness, and you get a saint. Add narcissism, manipulativeness, and cold-heartedness, and you get Elmer Gantry – or Jim Jones.

…..

Post-script: In “The Wisdom of Psychopaths” we meet Andy McNab, who scores very high on the psychopathy rating scale, and whose social roles have included those of highly decorated hero of the SAS (British Special Forces) and successful author – a “good psychopath” if there ever was one.

After writing the review, I came across the following: “The Good Psychopath’s Guide To Success:” How to use your inner psychopath to get the most out of life, by Dr. Kevin Dutton and Andy McNab, MCM, MM. Apostrophe Books, 2014.

I haven’t read it, but the opportunity is clear – put away your chainsaw and open your brokerage account, and the sky is the limit.

relies on fieldwork that take place in far flung locations. The researchers must develop productive working relationships with their study subjects, while trying to decide if what they are learning from their informants is accurate or highly subjective. Obviously, this is not easy to do and takes enormous time, patience, and strong observational skills.

relies on fieldwork that take place in far flung locations. The researchers must develop productive working relationships with their study subjects, while trying to decide if what they are learning from their informants is accurate or highly subjective. Obviously, this is not easy to do and takes enormous time, patience, and strong observational skills.

Security Agency. Traveling with them in Europe are Kira, their 19 year old first born, and her younger brother, Tony. One evening in Paris, Kira and Tony meet a good looking French graduate student named Jacques. Kira is attracted but unfortunately, the family is leaving for Spain the next day. Jacques offers to follow them to Spain and meet Kira in a famous bar he knows of. Jacques is not what he seems and things go downhill for Kira. No spoilers here, but this story has more twists and turns than a curvy mountain road and somebody ends up dead. It is available in large print at the RVM Library as are two of the John Wells series.

Security Agency. Traveling with them in Europe are Kira, their 19 year old first born, and her younger brother, Tony. One evening in Paris, Kira and Tony meet a good looking French graduate student named Jacques. Kira is attracted but unfortunately, the family is leaving for Spain the next day. Jacques offers to follow them to Spain and meet Kira in a famous bar he knows of. Jacques is not what he seems and things go downhill for Kira. No spoilers here, but this story has more twists and turns than a curvy mountain road and somebody ends up dead. It is available in large print at the RVM Library as are two of the John Wells series.

period of time in Mali, they were very different in scope and style and subject matter. Asifa’s job became an effort to train the Malians to grow Moringa, a miracle tree whose leaves cure whatever it is that ails you including malnutrition and arthritis. This was to be done, as Asifa says, all in a simplified Bambara. And David’s task was to help promote and improve a radio station 20 minutes away by bicycle, speaking French (which David had learned long ago but hardly remembered).

period of time in Mali, they were very different in scope and style and subject matter. Asifa’s job became an effort to train the Malians to grow Moringa, a miracle tree whose leaves cure whatever it is that ails you including malnutrition and arthritis. This was to be done, as Asifa says, all in a simplified Bambara. And David’s task was to help promote and improve a radio station 20 minutes away by bicycle, speaking French (which David had learned long ago but hardly remembered). by Bonnie Tollefson

by Bonnie Tollefson

Jonathan spent 3 years there during his time in the Peace Corps and also did a Masters project for the University of Minnesota on the effect of logging in the area on songbirds. As he was trying to decide on a subject for his doctoral dissertation, it came down to aiding the conservation efforts for two birds – the hooded crane and the fish owl. Since that hot buggy bog was prime hooded crane habitat he decided to study the fish owl. Never heard of a fish owl? It is the largest of the owl family being over two feet tall with a six foot wingspan and scruffy brown feathers that blend very well into their forested habitat. Their primary food source is fish and frogs so their hearing is not as good as other owls. The easiest time to locate them is February when they leave their distinctive tracks on the side of rivers and make their eerie duet calls during mating. These facts led Slaght to spend five winters in the forests of the Primorye as he located nest trees, studying habitat, and captured live owls. He took measurements, finally discovered how to tell apart the male and female (it’s more white tail feathers), banded birds and, on a few owls, placed expensive GPS transmitters to determine flight patterns. In spite of bears, tigers, and temperatures well below 0, Slaght and his Russian research assistants were able to work out a conservation plan for loggers and others to protect this owl found only in Russia and northern Japan.

Jonathan spent 3 years there during his time in the Peace Corps and also did a Masters project for the University of Minnesota on the effect of logging in the area on songbirds. As he was trying to decide on a subject for his doctoral dissertation, it came down to aiding the conservation efforts for two birds – the hooded crane and the fish owl. Since that hot buggy bog was prime hooded crane habitat he decided to study the fish owl. Never heard of a fish owl? It is the largest of the owl family being over two feet tall with a six foot wingspan and scruffy brown feathers that blend very well into their forested habitat. Their primary food source is fish and frogs so their hearing is not as good as other owls. The easiest time to locate them is February when they leave their distinctive tracks on the side of rivers and make their eerie duet calls during mating. These facts led Slaght to spend five winters in the forests of the Primorye as he located nest trees, studying habitat, and captured live owls. He took measurements, finally discovered how to tell apart the male and female (it’s more white tail feathers), banded birds and, on a few owls, placed expensive GPS transmitters to determine flight patterns. In spite of bears, tigers, and temperatures well below 0, Slaght and his Russian research assistants were able to work out a conservation plan for loggers and others to protect this owl found only in Russia and northern Japan.

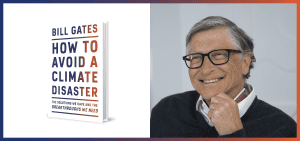

As an example, truck drivers constitute the largest occupational group in twenty-nine of our fifty states. They are at risk of losing their jobs as a result of autonomous vehicle technology. Another example: surgeons are beginning to use robots to assist with delicate operations.

As an example, truck drivers constitute the largest occupational group in twenty-nine of our fifty states. They are at risk of losing their jobs as a result of autonomous vehicle technology. Another example: surgeons are beginning to use robots to assist with delicate operations.