Posted in N&V

Collected Ideas for Activities for Visiting Grandchildren

by Joni Johnson information coming from from Barbara Maxfield and Jerry Richmond.

Here are ideas collected from RVM residents in February 2022 and updated March 2024 – More can be found through Google. Skip will be putting this list on http://rvm.closereach.com/favoritesset.html

. It’s not there yet, but it will be soon. However, you have access to this information now with the Complement. The best idea for time with your grandchildren is to spend quality time with just them, enjoying cooking, reading, gardening together or just walking the grounds at RVM to spot turkeys, quail, ducks, deer and rabbits. Here are some other ideas.

MEDFORD AND SURROUNDING AREAS:

MEDFORD RAILROAD PARK (541-613-1638) (open April-Oct; limited times so call in advance)

SCIENCEWORKS HANDS-0N MUSEUM

1500 E Main St, Ashland (541) 482-6767

Wed-Sun from 10am-5pm

Adults 12.50, Child 10.50 (Special rates on first Sunday)

THE CHILDREN’S MUSEUM

Arts and crafts, STEAM-based play, maker space, special programming

413 West Main Street, Medford (541-772-9922)

Tuesday-Saturday, 10am-5pm

Children 15.00; Adults 10

HARRY & DAVID’S FACTORY tour – tours run Monday-Friday at 9:15am, 10:30am, 12:30pm,

and 1:45pm Call ahead for reservations (877) 322 8000

ROGUE ROCK GYM (all levels of rockclimbing)

3001 Samike Drive – (541) 245-2665)

Day pass: adults 20, youth 18

CRATER ROCK MUSEUM at Central Point

Crater Rock Museum houses the finest displays of rocks, minerals and gems on the West Coast.

2002 Scenic Ave, Central Point, OR 97502-2185

Adults 7, seniors 6, students 5

ROGUE VALLEY FAMILY FUN CENTER (by the Expo)

Large indoor/outdoor entertainment hub with arcade games, rides, mini-golf & dining options

1A Penninger Rd, Central Point – Opens 12PM (541) 664-4263

ROGUE X

901 Rossanley Drive, Medford (541-774-2400)

State-of-the-art aquatics and events center with two water slides, pool with interactive play structure and outdoor splash pad

Open Swim Hours: Monday-Thursday: 11:30am-1:30pm; 6:30-8:30pm

Friday: 11:30-1:30pm, 3-5pm, & 6-8pm

Saturday: 11-1pm, 2-4 pm & 5-7pm

Sunday: 11-1pm, 2-4 pm, 5-7 pm

Drop-in fees: youth 5 (resident) or 6 (nonresident); adult 7 (resident) or 8 (nonresident); senior 5 (resident) or 6 (nonresident)

BEAR CREEK PARK – Playground – Siskiyou Blvd

There is so much at this park – a lot of grass, trees for shade, a skate park, tennis courts, kids climbing playground, bathrooms (clean for public park), paved path for walking/bike riding.

COUNTY FAIRGROUNDS – Entertainment area at entrance, Central Point

ROGUE VALLEY EQUESTRIAN CENTER – horseback riding by appointment -1663 S Stage Rd.,

Medford

SKATEBOARD PARKS in Medford (in Bear Creek Park), Talent and Ashland

SPLASH PARKS (usually open from Memorial Day to Labor Day) – recommend were:

DON JONES MEMORIAL PARK – 223 W Vilas Rd, Central Point – (541) 664-3321

FICHTNER-MAINWARING PARK – 334 Holmes Ave, Medford

WALKS AND HIKES:

RVM CAMPUS – walk the dirt road below the west side of the Plaza and look for

squirrels, deer, jackrabbits and deer; acorn woodpeckers, jays and other birds.

BEAR CREEK GREENWAY – walking and bike path – many approaches (see website map)

LARSON CREEK PATH – nearby, parallels Barnett Road and extends east from the

Bear Creek Greenway through primarily residential neighborhoods to North Phoenix Road – enter from Ellendale or Junipero

LITHIA PARK in Ashland – beautiful gardens, trails and playground

BRITT LOOP TRAIL from Britt Park parking lot (Jacksonville) – several trails

ROXY ANN and TABLE ROCK Hikes

FURTHER AFIELD:

OREGON CAVES https://www.nps.gov/orca/index.htm – Cave Junction, OR 97523

LAKE OF THE WOODS – 43 miles East of Medford toward Klamath FALLS – a natural lake near the crest of the Cascade Range in the Fremont-Winema National Forest

MacGREGOR PARK at Lost Creek (Highway 62) and then follow the road first

to visit the fish hatchery and then beyond to the top of the dam.

PACIFIC CREST TRAIL (go up Hwy 66); walk part of the trail; lunch at Green

Springs Inn.

THE GLASS FORGE GALLERY & STUDIO (glassforge.com)

501 SW G Street, Grants Pass (541-955-0815)

Monday-Friday 8am-5pm; Saturday 10am-4pm

WILDLIFE IMAGES in Merlin (near Grants Pass) animal rehab center – 11845 Lower River Rd, Grants Pass (541) 476-0222

THE BEAR HOTEL

2101 NE Spalding Ave, Grants Pass

Call 541-479-3351 to schedule a tour Monday-Friday at no charge

ALPACA RANCH at Lone Ranch (541) 821-8071 Reservations

13856 Weowna Way, White City, OR 97503-8535

HELLGATE JETBOAT EXCURSIONS – 966 SW 6th St, Grants Pass 541) 479-7204

CRATER LAKE & walks along Rogue River (Hwy 62)

WILDLIFE SAFARI – 600-acre zoo with animals from around the world & a 4.5-mile drive-thru

loop – 1790 Safari Rd, Winston, OR 97496

MOUNT ASHLAND SKI PARK- Just google it!

Oh No! Not Another Bleeping Disaster!

By Bob Buddemeier

[I have drawn on others for facts; errors and opinions are mine alone – RWB]

I have always been fascinated by the power of Nature, especially when manifested violently and/or extensively. Any kind of storm, volcanoes, earthquakes, wildfires – all are engrossing, as are the impacts as well as people’s preparations and responses. History indicates that we (technologically advanced modern humans) are much better prepared to deal with natural disasters than our forebears were. We now have forecasters and fire engines, helicopters, emergency agencies and supplies, near-real-time earth observing satellites, long distance communications, etc., etc. A couple of millennia ago, there wasn’t much people could do except sacrifice a virgin and hope for the best.

Given the apparent invincibility of technology, it was exciting to come across a natural event that offered no significant danger to primitive people, but posed an existential threat to Homo technicalis. On February 26, The New Yorker posted online What a Major Solar Storm Could Do to Our Planet, by Kathryn Schultz. (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/03/04/what-a-major-solar-storm-could-do-to-our-planet). In the best New Yorker tradition, it is 8,334 words long. I will summarize the key points more succinctly, and then take the discussion somewhat further than the article does. Quotations, unless otherwise attributed, are from the article.

Like Earth, the Sun has a fluid surface layer, but the Earth’s consists of air and water, whereas the Sun’s is plasma – a nuclear-fueled ultra-high-energy soup of ions and electrons. Like Earth’s fluid surface, the Sun’s surface is subject to storms, but although we have developed a pretty fair understanding of the how and why of Earth storms, we haven’t gotten much past observing the symptoms (like sunspots and solar flares) in figuring out solar storms.

Sunspots – an indicator of solar activity and storms — can occur anywhere on the Sun’s surface, with a frequency varying over an 11-year cycle (a maximum is due within the next year). Large sunspots indicate major storms. (https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/)

Sunspots – an indicator of solar activity and storms — can occur anywhere on the Sun’s surface, with a frequency varying over an 11-year cycle (a maximum is due within the next year). Large sunspots indicate major storms. (https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/)

What is a Solar Storm? When the magnetic lines of force on the rotating sun get tangled up, a storm occurs with one or both of two results: a solar flare, where the storm emits a pulse of high energy photons (gamma rays, X-rays, light); or a coronal mass ejection, which ejects a huge cloud of solar plasma. A large flare and a large ejection occurring together constitute a major storm. The effects we will be talking about occur when a major sunstorm ejects photons and plasma directly toward Earth.

What are the effects of a Solar Storm? – General and space-based: On Earth, the major effects stem from the interaction of the Earth’s magnetic field with electromagnetic effects of a strong flux of photons and of charged particles. The biggest effect that is directly detectable by humans is the occurrence of strong auroras at much lower latitudes than usual (as far south as central Mexico, and with daylight intensity in midcontinent North America). That would have been the only effect experienced by pre-technical populations, although it undoubtedly had a major psychological impact (oops, there goes another virgin).

The effects of electromagnetic disruption on the electrical and electronic systems upon which modern civilization depends would be at least temporarily disabling. For that reason, the major military powers have developed EMP (Electro-Magnetic Pulse) weapons that produce results similar to a solar flare, but with greater intensity over a smaller area (see https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/Documents/Pubs/320-090_elecpuls_fs.pdf).

The Earth’s magnetic field shields us from most of the hazards of solar and cosmic radiation by deflecting charged particles to the poles. For objects (e.g., satellites) or people (e.g., astronauts or extraterrestrial colonists) outside of the Earth’s magnetic field, radiation can pose a destructive or lethal threat. Neither the moon nor Mars has a magnetic field, so radiation is one of the greatest barriers to extended space exploration. Closer to home, the damage to the massive inventory of communication, positioning and remote sensing satellites will disrupt far more capabilities than most of us can imagine. For these, as well as Earth-based facilities, shutting down the equipment can reduce (but not eliminate) vulnerability– if there is enough warning to safely do so.

What are the effects of a Solar Storm? – Earthbound specifics: The effects of a major sunstorm will be the shutdown, and possible destruction, of facilities and equipment that provide or depend on electricity. Long conductors, such as extensive power and communication grids, are especially vulnerable. We know that the effects of a geomagnetic storm will be affected by geology, geography, and the design, siting, and operation of equipment, so there will be a patchwork of effects, with some things destroyed, others damaged, and some just turned off — including local, freestanding facilities as well as large systems. In 2008 the National Academy of Sciences reported “…that much of the country’s critical infrastructure seemed unlikely to withstand [a maximum solar storm]. Extensive damage to satellites would compromise everything from communications to national security, while extensive damage to the power grid would compromise everything: health care, transportation, agriculture, emergency response, water and sanitation, the financial industry, the continuity of government. The report estimated that recovery from a [G5+] storm could take up to a decade and cost many trillions of dollars.” Preparedness has improved since then, but many of the vulnerabilities – and uncertainties – still remain.

What can be done, and are we doing it? – National and Global: There are solar observatories that keep a constant watch on the sun (see the New Yorker article, and https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/phenomena/coronal-mass-ejections), with people standing by to relay a warning if dangerous symptoms appear. However, the leading edge of a solar flare can reach the Earth in less than ten minutes, and cause the loss of many radio communication frequencies due to ionization of the upper atmosphere. Less than a day later, and potentially lasting for at least two days, the cloud of energetic particles from the coronal mass ejection arrives. That scrambles the Earth’s magnetic field, and initiates the geomagnetic storm that has the potential for causing the critical shutdowns.

Some critical facilities and functions (the military, Homeland Security, and communication- or power- intensive organizations) have plans in place, although they are not usually publicized because of national security issues. In terms of issues most relevant to the general population, there is…” a federal directive that, as of this January, requires every provider of bulk power to have a plan in place to deal with a “benchmark geomagnetic disturbance event.” That directive is important, but the benchmark itself is troubling. It was established by using thirty years of magnetic-field data to extrapolate the likely magnitude of a once-in-a-century storm. The resulting standard is clear, uniform, achievable, extremely useful during most solar storms, and wholly inadequate for severe ones.”

The reconstructed record of major storms identifies 1859, 1872, and 1921 as (pretechnology) years of severe events, with numerous other smaller ones that were still able to do perceptible damage. None of those three largest historical storms identified are included in the past thirty years, or occurred under present conditions of technical development.

What can be done, and are we doing it? – Local and Personal: In spite of emphasis on emergency preparedness, a majority of individuals, small businesses and local agencies are not well prepared for the more familiar disasters, and many may not even be aware that solar storms are an issue. The precautions recommended for natural disasters are qualitatively appropriate for a solar storm response – preparation to be without utilities, food and water, communications and transportation. However, when scale is considered, the preparations useful for Earth-based disasters are quantitatively inadequate for a major solar storm.

A G5 solar storm (the biggest imaginable, like an F5 tornado or a Category 5 hurricane) will affect the entire planet. By contrast, the area that would be affected by the Cascadia earthquake is about 240,000 square miles – a miniscule fraction of the area affected by the solar storm. In spite of the scale difference, estimated probabilities are very similar: for the G5 solar storm: a 12% chance in the next decade, and for the Cascadia Great Earthquake, a 37% chance in 50 years. These differences and similarities dramatically change considerations of what to do and how to do it.

What to think (or worry) about: We are considering an off-the-charts G5 storm, which no living adult has ever experienced. However, we can’t really predict many details. Nor can we count on local or regional assistance, even if relatively prepared.

” …because solar storms affect an unusually wide geographic area and an unusually broad range of technologies, they are more likely than other disasters to cause cascading failures… They can affect large areas of the world, which minimizes access to outside help in the aftermath. If an earthquake devastates Los Angeles, aid can pour in from neighboring regions. But, if a solar storm devastates New York, anywhere close enough to help will likely be devastated, too… [And,] because space weather affects so many technologies, a severe storm could expose dependencies among them that we did not fully appreciate, or did not recognize at all. Our vast and interrelated technological infrastructure could turn out to harbor a single point of failure—a component, no matter how central or trivial, whose malfunction shuts the whole thing down.”

The size of the affected area determines the rate at which assistance arrives or recovery can occur. Depending on location and season, prolonged isolation could result in breakdown of services, loss of governmental control, anarchy, and famine. In addition to crime, movement of refugees from one area to another could be another disaster-compounding factor. Internationally, the recent pandemic demonstrated some of the risks inherent in globalization; damaging or devastating much of the planet would take that several large steps further. World order, as well as local, would be threatened if larger or better armed states or groups invade their neighbors in search of scarce resources, or as pre-emptive self-protection.

What to do: (1) Think and plan for the solar storm contingency; since the fuel pumps and charging stations won’t work it’s probably best to shelter in place, or at least close by. (2) Reconsider your level of preparation – if you now have three days of supplies for that multi-week emergency, you might want to up the inventory a little for the multi-month event. (3) Form or join a compatible mutual support and assistance group. Safety in numbers can take many forms. (4) A solar generator that is not connected to a power grid stands a good chance of surviving a solar storm. Although it would require significant space and money, its benefits beyond just sunstorm preparation might justify consideration (see https://thecomplement.info/2023/08/28/the-limits-to-emergency-solar-power/).

And if all else fails, check around for some expendable virgins.

Saving the Earth Bit by Bit

Sustainable Products- Why, Were and How

By Joni Johnson

Gini Armstrong, the intrepid leader of the Green Team, and I, talked about sustainable products. Until then, I was ignorant about how many kinds of products were available to help save our planet from plastic etc. at very reasonable prices. This article will explore some of them. You will also have a chance to see some of them at our Earth Day Event on April 22 from 1-4 pm. hillTopics will have an article devoted to this event in their April Edition. The event includes speakers, tables and booths which are topically focused. And one of those tables will be specifically targeted towards sustainable products.

Gini noted that plastic bottles and jars not only negatively affect our environment, but they also increase the price of the items in two ways: 1) the liquid product inside the plastic often includes 80-90% water; and 2) the product costs more to ship because of the weight of the liquids. In many cases, similar products are available in powders, tablets or sheets rather than liquid form.

In terms of the environmental effect, it actually takes more water to create a plastic bottle than all the water that is in the liquid product it contains, which is already quite a bit.

While we have often been seduced by the idea of convenience, most of the sustainable products are more convenient and much more easily stored because of their smaller size. Throw-away plastic bottles are particularly damaging to the environment, so the Green Team hopes that people will switch to reusable metal water bottles or at worst, plastic bottles that are considered less damaging. Gini is glad to see increasing numbers of residents using refillable bottles and insulated cups instead of the single use ones for coffee.

When one does use plastics, look for these codes which are considered safer: BPA free, #2 HDPE, #4 LDPE, and #5 PP. Examples of #2 HDPE (high density polyethylene) include containers used for milk, water, juice, and yogurt cups. #2HDPE is also used for some plastic bags.

Examples of solid rather than liquid products include shampoo and conditioner bars and laundry sheets or strips. Gini has been using some of these products for years. She says they work perfectly and points out that there are many kinds of shampoo/conditioner bars for various hair needs. She also loves her compressed laundry detergent, which comes in sheets, which she says is much easier to store because of its smaller size, and cheaper because it costs less to ship than liquid detergent.

Gini tends to use Amazon for her purchases. Although there are many brands to choose from, for the shampoo and conditioner she uses. (Just touch on the picture to go to the Amazon page where each product is found)

For laundry detergent, she uses Tru Earth:

Here are links to other products. For more options just go to Amazon and type in sustainability products. I think you will be amazed at what is available, and you might find just the thing that will fit the bill in your homes. These are just some of what I found. I was looking for products with high approval ratings.

For Detergent Products – At 4.5 approval, is Dropps Dishwash detergent pods

For Facial cleaning at 4.8 approval is Tidalove Daily 3 in 1 Facial Cleanser, Exfoliator and Wash-off Mask,

For Natural Soap bar for dishes at 4.4 approval is a company called Zero Waste:

Natural Sponges – 6 Pack of EcoFriendly Biodegradable Coconut Sponges – Multipurpose Kitchen Sponges – by American Kitchen Company ™ at 4.5 approval :

At 4.6 approval are natural bamboo sheets for facial cleaning:

There are so many more to be discovered. Check them out and see what you think. And don’t forget Earth Day on April 22 from 1-4 in the Auditorium.

The Many Services Related to Dining

by Bob Buddemeier

Ken Wilson has the job that everyone wants somebody else to do well. As Ken explains, it was an example of the adage “be careful what you wish for.” He applied to serve on the Dining Services Advisory Committee (DSAC), and somehow came out of the process as Chair of the committee.

After serving in the position since October, Ken felt ready to talk to The Complement about DSAC’s current activities. His first statement was to acknowledge and thank Janet Jacobson for her three-year service as Chair, and especially for negotiating the changing restrictions and other challenges of the COVID period.

Ken Wilson

When asked what he saw as the main thrust of committee activities, he unhesitatingly answered “communication” – enabling the committee to effectively assess resident needs and concerns and transmit them to RVM Administration and staff, and to assist with providing Dining Services information to the residents.

An example of actions taken to better understand resident viewpoints is the appointment of individual committee members to take responsibility for talking to residents in the various dining venues. These assignments are: Arden – Claudia Macmillan; Umpqua and Mountain View – Meridel Hedges; Manor dining room – Gary Jensen; and Bistro – Diane Friedlander. They communicate their observations and information collected from the residents to Marilyn Perrin, who compiles them as feedback for the committee and Dining Services leadership. Vicki Gorrell has also continued in the invaluable job of secretary, producing minutes and posting activities on MyRVM. Ken has also welcomed Sally Densmore to the committee as a replacement for Madge Walls who recently resigned for personal reasons.

Ken has weekly meetings with Eric Eisenberg, and the full committee (which includes Eric and Dave Keaton in addition to Resident Council officers and RVM board members) meets at 1:00 pm on the third Wednesday of every other month (January, March, May, July, September and November In 2024), with smaller meetings in the intervening months. When asked if guests could attend the regular meetings, Ken said “Yes, certainly, but if they want to present or discuss something, I’d like them to contact me before the meeting.”

In addition to acting as advisors and communication pathways, Ken pointed out that the committee can provide active support for Dining Services. The example he gave was the period when Arden needed to close down for a few days. Reservation holders needed to be notified, and there was not enough staff time available for them to do it in person. The committee divided up the people who needed to be contacted and informed them with personal phone calls instead of a memo or email.

These kinds of activities can help smooth the interactions between Dining Services and the residents, while giving everyone a better understanding of DSAC’s goals and capabilities, Ken said. This is good, since there will certainly be lots of communication opportunities associated with developments such as the “declining balance” (aka Spend Down & My Choice) meal charges, which Dave Keaton has announced will be initiated March 1.

For further information about DSAC and what it does or can do, contact Ken or one of the committee members named above, Mission, membership and minutes are posted on MyRVM; click the main menu Dining tab, scroll all the way to the bottom of the page, and click the icon in the lower right corner.

Getting There — and Back Again — in Winter

by Joni Johnson and Bob Buddemeier

Even though we don’t experience much snow in winter, we still get days of snow and ice, and recently, a lot of fog. It is wise to review the important safety-related dos and don’ts about driving and walking in winter conditions. This is certainly true for anyone new to this area, but also a good reminder for those of you who have been around a while.

Walking in winter:

If it is, or may become, dark or foggy, wear high-visibility clothing. This is a good idea even in daytime; heavy clouds and dirty windshields make for poor visibility. Fluorescent “construction” vests are good and inexpensive; available in stores or mail order.

Consider wearing or carrying a visible light – available at Manor Mart. A flashlight in your vest pocket is also a good idea, especially if you don’t use a wearable light. And don’t forget your phone (which probably has a flashlight).

If it’s slippery, stay home or use Manor Transport. However, if you absolutely have to take Arfy out for a walk, it would be good to have ice/traction cleats to put on over your shoes:

https://www.consumerreports.org/health/ice-cleats/best-ice-cleats-a8085230677/

https://reviewed.usatoday.com/accessibility/features/non-slip-ice-cleats-elderly-disabled

Even if you don’t normally use them, a trekking pole (or two) might be good if there is real snow, slush or mud – but maybe not for ice unless your sticks have pointy ends.

Driving in Winter:

Equipment – as to vehicles, all-wheel drive is better than front-wheel drive, which is better than rear wheel drive. 4-wheel drive is good for off-road, low speeds or heavy towing but NOT the best for normal driving under slippery conditions. One absolutely essential piece of gear is a good flashlight with fresh batteries; other things to have in your car are discussed below.

In typical winter conditions, vehicles rated at 10,000 pounds gross vehicle weight (GVW) or less, and not towing or being towed, are allowed to use traction tires in place of chains. However in very bad winter road conditions all vehicles may be required to use chains or cables regardless of the type of vehicle or type of tire being used. This is known as a conditional road closure. A conditional road closure may occur on any of Oregon’s highways and is frequent in the winter on Interstate 5 through the Siskiyou Pass south of Ashland – so have a set of chains or cables.

“Traction Tires” are studded tires, retractable studded tires, or other tires that meet the tire industry definition as suitable for use in severe snow conditions.

https://www.tripcheck.com/Pages/Chain-Law

Winter driving tips: conditions and then have found various you-tube videos that will explain more thoroughly how various conditions affect your braking capabilities, how a 4-wheel drive affects driving in difficult conditions and most importantly, how to deal with skids on icy and snowy roads.

The six most important tips for driving in the winter are:

- Plan Ahead- know what the weather conditions might be- even if you are just going to Ashland or Jacksonville. What is the predicted temperature? Is snow, rain, or expected?

- Accelerate and decelerate slowly. Otherwise, the tires will spin. Use low gear going downhill to reduce the need for braking.

- Slow down. If the speed limit is 55 or 65 mph, you may only want to be going 30 and certainly no more than 45 mph. Take curves very slowly under slippery conditions; rear-wheel drive cares are especially prone to spin-out.

- Increase your following distance to double or even triple the distance you usually allow so that you can decelerate slowly and not have to brake abruptly, which will quite probably send you into a spin or into the vehicle in front of you.

- Try to avoid coming to a complete stop on a hill, and if you have to, leave lots of room around you. However, it is better to continue moving slowly rather than coming to a complete stop if that is possible; if not get off the road if possible and turn on your warning flashers.

- In fog, use low-beam headlights with fog lights if you have them. Do not use fog lights alone unless your tail lights turn on with them. If you are moving very slowly or stopped (on or off the road), turn on your warning flashers.

Here is a video that explains how various weather conditions affect the grip of your tires to the road and therefore how fast you can stop: https://youtu.be/7t_sYFBYCKs

Finally, one of the most important things to know when driving in bad weather is how to avoid sliding on slippery roads, and if you are caught in a skid, how to correct one without damaging yourself, your ego or your car: https://youtu.be/TZQXuWzBC18

If you need any more suggestions, there are many YouTube videos and other sources of information on the internet. Put in “driving in icy (or snowy, or foggy) conditions” or whatever else you are interested in, and take your pick.

Additional notes:

Keep your car at least half full of fuel (or half-charged)

Driving around town (defined as locations where you will be within 100 yards of an occupied building) – In addition to the flashlight, other things to have in the car are your telephone(s), and warm clothes and walking shoes/boots if you don’t always wear them when driving around.

Long distance travel – Be prepared to survive for at least 24 hours if you are isolated in your car due to snowstorm, accident or land/snowslide. That means being able to: stay warm and dry after the fuel is consumed and signal for help (phone, lights and auto phone charger). Having an entrenching tool and some water and a minimal food supply is also very desirable.

Yes Virginia, RVM Does Have Geysers

By Joni Johnson

I live at the end of Horizon Lane. Going to Arden on Friday, November 17 about 5 pm, I noticed an enormous amount of water spewing down the road and pooling quite vigorously in front of Malama Way. By evening it seemed to have stopped. Saturday was a different matter. I woke up to an enormous geyser almost fifteen feet high (see Jill Stoecker’s impressive photos). Naturally, I rushed to the street to see it in person. Luckily, so did Drew Gilliand and his crew.

We have two water pipes running under our street. One is fire hydrant water and the second is our  domestic water. After realizing that the problem was linked to our domestic water lines, they turned off our water to all of the cottages on the 1100 and 1200 blocks for what was supposed to be six hours. I was already checking to see if I had any spare water available for drinking and immediate use in case it took longer than expected. And Drew was offering water in case it was needed. But lo and behold, it was done in three hours. The water was back in the pipes, and we just had a metal covering over the hole in the road to deal with when driving down Horizon. It turned out that the failure of the extension from the fire hydrant pipes which had caused the first leaks had also created a problem with the extension from the domestic pipes and that caused our geyser. In fact, the root cause of the leaks was failed connectors between air relief valves and the fire and domestic water line.

domestic water. After realizing that the problem was linked to our domestic water lines, they turned off our water to all of the cottages on the 1100 and 1200 blocks for what was supposed to be six hours. I was already checking to see if I had any spare water available for drinking and immediate use in case it took longer than expected. And Drew was offering water in case it was needed. But lo and behold, it was done in three hours. The water was back in the pipes, and we just had a metal covering over the hole in the road to deal with when driving down Horizon. It turned out that the failure of the extension from the fire hydrant pipes which had caused the first leaks had also created a problem with the extension from the domestic pipes and that caused our geyser. In fact, the root cause of the leaks was failed connectors between air relief valves and the fire and domestic water line.

The next day (December 4) , I found a worker getting rid of the wet earth and replacing it with new fill so that they could eventually pave over the street. The reason for the new fill was to keep the paving dry enough so that it wouldn’t sink in that spot.

Other than a few garages having to deal with some leakage (which the facilities crew worked on, brought fans and dehumidifiers and redid the wooden molding where necessary) no one else had any property damage. For residents, it was a little exciting blip to our weekend. Another great reason to live at the Manor.

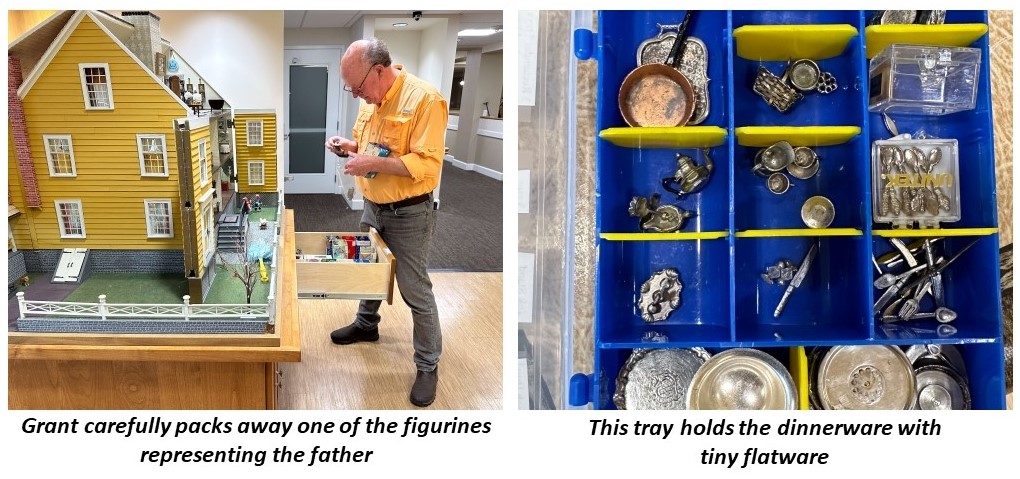

The Storybook House

by Robert Mumby

With the enclosure removed the house is ready for its Christmas scene.

The “doll” house on the manor ground floor next to the gym and bistro is a museum quality display of a New England home and its residents in 1893, created by Joanna Becker. A plaque on the side of the house enclosure provides more details about the house that is now the property of the Manor.

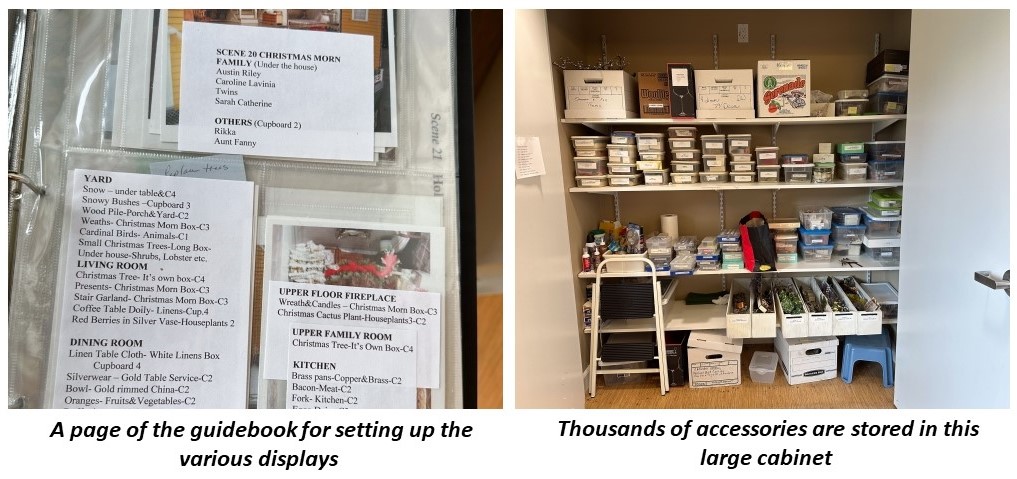

A collection of decorations and accessories is used to portray twenty-one scenes depicting holidays and family occasions. A group of Manor residents care for the house and change the scenes. Of the pre-covid committee, only Yoka Koch remains, and is assisted by her husband Grant. During the Opportunity Fair, three new volunteers joined the committee and were trained on the care of the display and making changes to it. With the additional help, more scenes can be displayed each year.

Yoka and Grant. Note the duster by the steps.

Many of the pieces are tiny and delicate, requiring a steady hand and sharp eye to handle and place in position.

But before setting up a room, it must be gently dusted. There is no top to the enclosure and once a ceiling leak dripped water into one of the rooms.

The bathroom and kitchen are hard to see when the house is in its corner. To the left of the bathroom is another room.

There a small mistake (Naturally it would be small.) in the Christmas setting. If you find and report the mistake to the author, you will receive a free compliment.

Let Me Entertain You!

by Sarah Karnatz, as told to Bob Buddemeier

Sarah Karnatz has been feeding and entertaining Manor residents for over a decade – first as the person in charge of catering, and more recently as Director of Community Engagement. She has put on thousands of events of all types and sizes, with a superb track record. So superb, in fact, that we became curious and asked if there were any events that were what are politely termed “learning experiences.” She graciously responded with the following accounts.

Semper Fidelis In 2012, Sarah was responsible for organizing the Marine Corps birthday ball in the Plaza. She recounted the preparations: “I had worked on this event for months, dialing in the menu, table linens, centerpieces, and I had countless meetings with the Marines tasked with this ball. We had every part of the night dialed down to the minute, from the posting of the colors, the cutting of the cake with the sword, to the Silent auction winners’ announcements.”

Since the Corps was first founded November 10, 1775, its birthday occurs when it is cold outside, and the heat is on inside. Therein lay the flaw – “The one thing I didn’t plan for was how hot the room would get with 120 well-dressed veterans and their elegant spouses! The room got so hot that people were shedding coats and sweating so much that everyone’s hair was matted to their head and make up was running off… it was SO HOT,” Sarah said.

What to do? Turn down the heating? The wall thermostat was in a locked plastic box, with no indication of where the key might be found. Open the door to the walkway? “When we opened the door, those that were close to the open door froze!”

Sarah said that after the event, she was granted a key to the thermostat box, and informed that there was an employee who could regulate room temperature – but needed a few days notice. An item to add to the preparation checklist.

The Hazards of Inclusiveness — over the years, Sarah has received many requests to have events in the Terrace circle so that the Licensed Facility residents could join in more easily. “Well, there is a reason I don’t host anything in that space,” she said. “During a large outdoor summer party we had a huge BBQ station set up on the Grill patio, a 5-piece band, a wine station, tons of chairs and popups all set up in the Terrace circle.”

Then the ambulance came….. since they couldn’t get into the circle, they had to park on the main road, walk over, and thread the gurney through the festive party-goers. Happily for all involved, there was no patient aboard when they came back out.

Needless to say, in retrospect that was considered a bad siting decision. Another item for the checklist — no blocking of any entrances!

The Caribbean cookout was quite an adventure. While serving Caribbean cuisine on the go sounded like a good idea at the time, poor planning and execution on the part of the food truck crew left more than a few things to be desired, resulting in some less than satisfied residents.

According to Sarah, “The Caribbean food truck staff assured me that they could handle a large crowd. They had NO idea what they were getting themselves into! The crew manning the booth had left ten minutes prior to start time to grab a speaker for music, when they could have just requested one from one of our crew working the event. THEY LEFT! Once serving finally started, wait times for food were about 2 days and 5 hours, give or take, with the line extending from the pocket lot around the front of the main manor roundabout almost to the terrace building! It was awful!”

Sarah, diligent as she is, had to reform the way they were serving food to each resident. If they had kept operating the way they were trying to, she said, a small fraction of residents attending might have gotten food served to them by sundown. However, Ian pouring Mai Tais for everyone in line lifted spirits and helped reduce the frustration.

Additional checklist items: (1) No Caribbean food truck ever again; (2) Have Ian, w/Mai Tais, on standby.