An editorial news item by Bob Buddemeier

Summary: I am stepping out of my role as Chair of RPG, and that position will be filled by Bob Berger. In addition, we have formed a Planning Group to help develop future organization and activities. I will continue to contribute, primarily by drafting an Operations and Information Manual for RPG, with some effort devoted to developing a semiannual cycle of Preparedness activities, This article addresses my motivations for these actions.

Joni Johnson has written an article on my intention to take less leadership responsibility in the Resident’s Preparedness Group (RPG). I found that I couldn’t fit everything I wanted to say into Joni’s excellent questions, so here’s an attempt to explain a few things about my motivations and intentions.

I remain committed to the idea of an RPG, and will continue. However, I am convinced that to serve the RVM community, an effective RPG organization needs to function as a team, and needs to be organized, managed and led in manners appropriate to that model. My views of what it means to be a community, organization, or team are given at the end of this article.

I have been unable to make adequate progress on either developing the organization or providing sufficient leadership. A change is needed, and fortunately, Bob Berger has agreed to step into the chairmanship. Bob, who has been serving as vice-chair, is well qualified for the job, and Dan Curtis will continue as Communication Lead. I will move into a role focused on assembling and making available the information needed by residents, and by the RPG volunteers.

To further the transition, we have recruited a Planning Group – Dan Wagner, Teddie Hight, Jim Macmillan, David Drury, Ann Rizzolo, and Scott Wetenkamp. Along with Ken Kelley (radio communications manager), the group is being challenged to help take the initial steps toward the next organizational structure.

There are proposals for two steps to be taken to help involve more people and build capabilities. One is to support the idea of a late-April community-oriented Preparedness Program that would be the counterpart of a similar fall program as part of a semiannual cycle. The intention is to provide topical foci for individual group members to develop more understanding and involvement, and to help create some useful interim products.

The second step is more ambitious, but one which I will undertake personally. Over the next few months, I plan to develop a working draft of an RPG manual, including current organization and procedures and essential background information. After 2.5 years of involvement I have access to a wealth of material, and a fair amount of experience to bring to bear. I hope to recruit a few people to assist with review and editing, but will proceed in any case

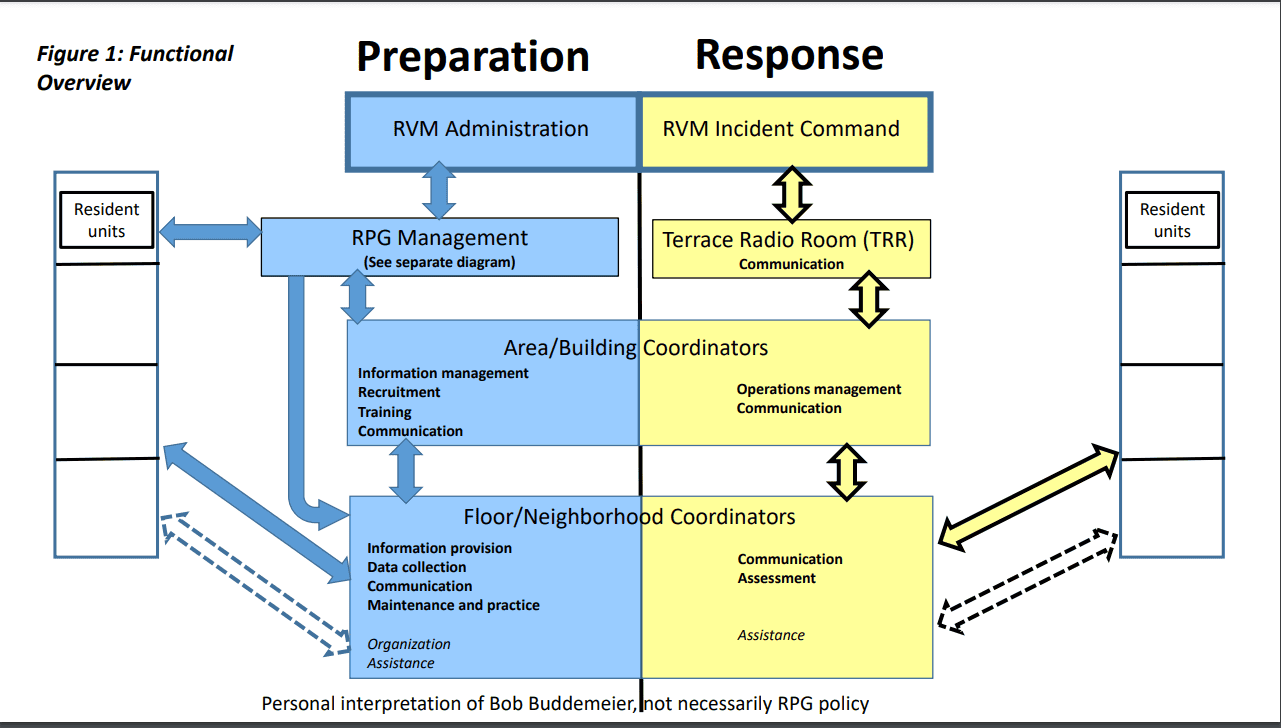

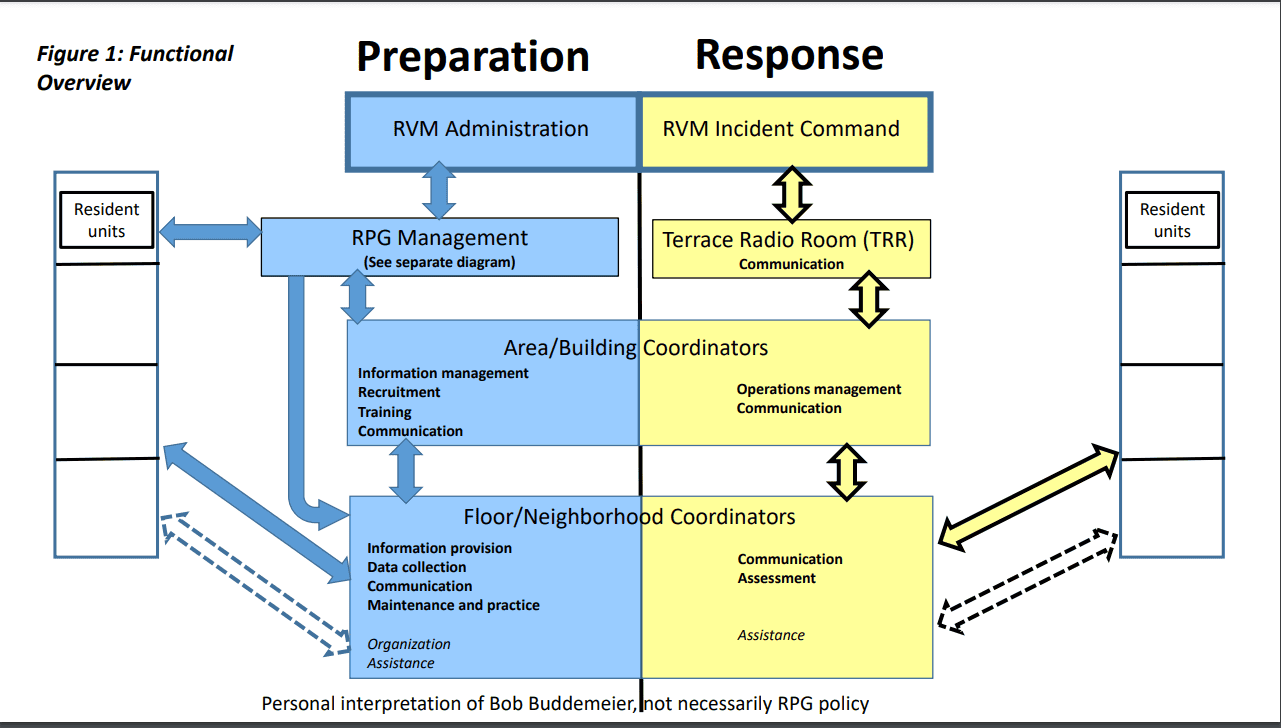

The goal is to present in useful written form the relationships and activities reflected in the Figure 1 diagram of RPG interactions.

More information will be forthcoming shortly. The following material amplifies on the basis for my approach.

Community – the following is an edited reprint of an article in an earlier issue of The

Complement.

Community is a term often used at and about RVM. What do we mean? The first entry that pops up from a google search of the internet gives us two choices:

- a group of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common.

- a feeling of fellowship with others, as a result of sharing common attitudes, interests, and goals.

RVM residents clearly qualify under definition 1 – we’re all here, we’re all old, all or almost all of us are US citizens, mostly upper-middle-class, and on and on. However, most of us would like to think of ourselves as a definition 2 community. Are we? And what might we do to increase that specific sense of “higher” community?

We have lots of subcommunities in the definition 2 sense; co-religionists, musicians, golfers, and more – but we don’t see them alloyed into a definable whole. Of late, we have had more general common feelings and attitudes of frustration, isolation, and powerlessness. That, however, is not the bonding experience we seek; it’s more on a par with inmates of the same prison.

Is there a way to encourage collective actions to solve common problems without building on – and thereby probably intensifying – differences in priorities among residents or between residents and administration? A focus on responses to external problems can build community both among residents and between staff and residents, and recent events have demonstrated that it works. This is the basis for the Residents’ Preparedness Group – protection of all residents from the common threat of an externally imposed emergency or disaster.

Teams – a model of groups within a community, and in the idealistic extreme, for the community as a whole.

Using the analogy of sports, teams are groups of people with a common goal, a variety of assigned roles, a rulebook for the game, a playbook for the team, and both a captain (operational tactical leadership) and a coach (longer term preparation and strategy). Team function requires commitment by individuals, and communication within the group. And maybe just a bit of discipline.

Organizations – we have lots, and all kinds. How do we create or identify those that will achieve what we want and need?

Teams are organizations, but not all organizations are teams. Many organizations are more like a chess board – a few power movers in the back row (sometimes only one) and a bunch of pawns out in front. The chess game is NOT an adequate model for RPG, where in order to function, ALL participants must be able and willing to exercise some judgment and initiative. Figure 2 provides some idea of the range of activities our volunteers exercise in order to support both residents and Administration in responding to emergencies.

Wildfires won’t wait, earthquakes will happen when they happen, and power outages are a fact of modern life. In spite of the barriers caused by the pandemic – a long-term emergency itself – we need to move ahead with preparation. Please support the RPG efforts.

Nectar Bartender: My new hummingbird feeders got no takers all summer. Now, in late November, I’ve suddenly got hummers galore. If Portland is where they migrate for winter, they must spend their summers at the North Pole. Is this yet another harbinger of climate doom?

Nectar Bartender: My new hummingbird feeders got no takers all summer. Now, in late November, I’ve suddenly got hummers galore. If Portland is where they migrate for winter, they must spend their summers at the North Pole. Is this yet another harbinger of climate doom?

Our native trees (think Doug fir or Sitka spruce), for all their stately majesty, suck at producing the nectar hummingbirds crave. The advance of civilization’s plow, however, brought with it lots of non-native flowering species (as well as a not insignificant number of easy marks like you) upon which the birds could thrive.

Our native trees (think Doug fir or Sitka spruce), for all their stately majesty, suck at producing the nectar hummingbirds crave. The advance of civilization’s plow, however, brought with it lots of non-native flowering species (as well as a not insignificant number of easy marks like you) upon which the birds could thrive.