An Infotorial by Bob Buddemeier

Foreword: This essay was stimulated by resident and Administration presentations on Earth Day. A significant part of my career was devoted to sustainability-related research. These are some of the things I think I have learned. I call it an infotorial because it combines my editorial comments with information derived from what I consider reliable sources. Remarks that are primarily opinion are labeled as such.

Caution: This may be somewhat depressing, but there is an upturn near the end

What does “sustainability” mean?

One commonly used expanded definition is:

- Sustainability is the ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- It involves the responsible management of resources to ensure social, economic, and environmental well-being for current and future generations.

- Sustainable practices aim to balance economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental stewardship to create a resilient and harmonious society that can thrive indefinitely within the constraints of our planet’s finite resources.

How do we apply this definition?

Most advanced definitions include economic, social, and environmental components of sustainability, as in the 3rd bullet above. For this discussion, we’ll stick to natural resources and the environment – they are complicated enough, and more measurable and manageable than the others. We’ll also start with a global perspective, and then come down to more practical scales.

In order to decide on policies or adopt specific procedures, we need quantitative values to establish goals, trends, or relationships. If the data doesn’t exist, we have to do research or make assumptions. Recent observations and predictions of environmental factors suggest that it may be critically important to take action promptly, which means making decisions soon – and therefore under conditions of uncertainty.

To consider some points in the 3-bullet definition above, we need to recognize that we are looking at moving targets: when I was born the world population was about 2 billion, and had far less environmental impact than the current population of 8 billion – or the predicted 11+ billion that will be on the planet when my recently-born great grandson is my age. That means resource demands are increasing, both for population support and for economic development.

Unavoidable resource depletions are occurring. Two basic examples are land and water. Available land and human infrastructure are being reduced by inundation and erosion due to sea level rise, and by the increasing areas with extreme temperatures or shifting precipitation patterns. Accessible potable water supplies are being reduced by glacial melting and snowpack reduction, human exhaustion of groundwater aquifers, and salt water intrusion (sea level rise). With the exception of aquifer depletion, these are natural processes with almost no prospects for stabilization or reversal.

Examination of options

Can we develop sustainability in a system with a steadily decreasing resource base and increasing demand? Answering the question requires a more detailed assessment of the factors involved. Let’s take a look at some of the key terms in the definitions above.

#1. Future generations – how many generations, how many total people? Opinion: The years 2050 (about one generation away) and 2100 (3-4 generations) have been the most common – and therefore data-rich – targets of environmental projections. Given the large uncertainties and the need for both prompt action and adaptive management, it is probably unrealistic to look farther ahead than a few decades.

#2. Needs (and well-being) – is that a middle class American lifestyle, or is it 2000 calories and a gallon of water per day, plus rudimentary shelter? At present, about 8% of the world’s population lives in “extreme poverty.” Malnutrition and food insecurity are not hallmarks of sustainability.

#3. Do we aim for the current distribution of wealth, or something more equitable? Regardless of what we want, what can be sustained in the long term?

Interim Conclusion [OPINION]

“Sustainability” Is an attractive abstract concept which has a vanishingly small chance of implementation at large scales of space and time. Used uncritically, it becomes a buzzword and a tool for greenwash (See Figure 1).Figure 1: Sustainability sells computers, but not necessarily vice versa.

Figure 1: Greenwash

The obvious need for sustaining our natural support systems makes it important to identify ways to put the sustainability concept into effective practice. Goals and methods need to be tailored to the existing social, economic, and environmental conditions in a region of manageable size and composition. There is no coherent consensus plan at the global scale, and little hope of developing one anytime soon. Since there is no one-size-fits all approach, we have to act on the premise that something is better than nothing, and initially on a local scale. These are the conditions under which the Green Team (picture at end of article) and RVM’s Strategic Plan are operating.

What to do – and how [Opinion]

[Topics are not necessarily in order of importance or execution.]

The most practical approach is to start with activities appropriate for individuals or small groups, and attempt to expand involvement and effectiveness on the basis of initial accomplishment. If local advocates are many and committed, political influence at higher levels as well as greater local accomplishments will be possible.

The exact sustainability issues addressed will necessarily depend on local needs and interests; water conservation, waste management and ecosystem protection (such as the pollinator projects) are obvious candidate categories. However, initial success should be measured primarily in terms of increased awareness and participation and activities selected with that in mind.

Community and organization building – once an identity is established, the following approaches are tested ways to proceed:

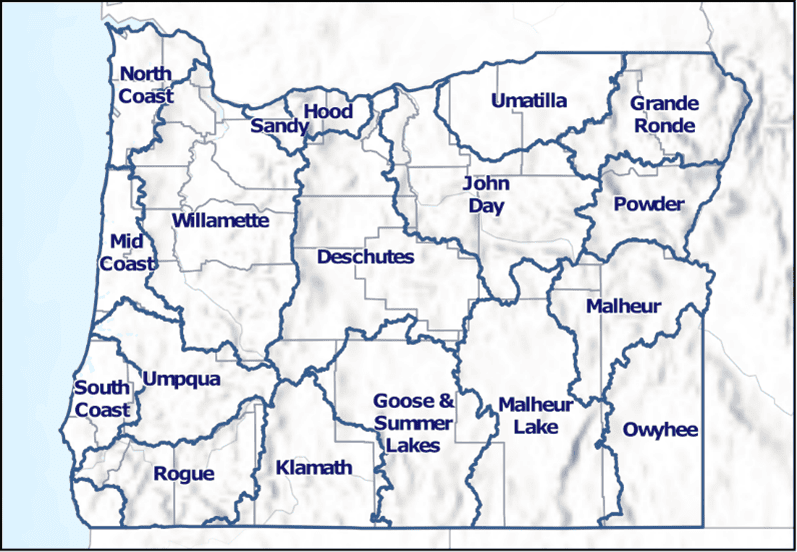

Figure 3 shows a template by which sustainability organization could be superimposed on political units. In the long run, water-supply units could be combined into regional groupings that would provide more manageable resources (e.g., SW Oregon could be the Umpqua, Rogue, and South Coast basins).