RVM DVDs on Aging and Dying

by Dave Guzzetta

Following the lead of the Book Library, the DVD Library has only a few documentaries about Aging and Dying, but a large collection of movies about Death, Dying & Grief.

These movies range from several irreverent comedies to some very serious and touching movies.

Documentaries About Aging & Dying

3530 How to Die in Oregon (NR, IMDb 8.3) In 1994 Oregon became the first state to legalize physician-assisted suicide. How to Die in Oregon tell the stories of those most intimately involved with the practice today — terminally ill Oregonians, their families, doctors, and friends — as well as the passage of an assisted suicide law in Washington State. (HBO Documentary)

1401 Dying Wish (NR) Karen van Vuuren is a former television and radio news producer. With the documentary Dying Wish, she has found a natural fusion of her journalistic talents and her knowledge of end-of-life issues. Karen has also worked in the field of elder care and for hospice. (29 minute Documentary)

1384 Alive Inside (NR, 8.2) Five million Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. A man discovers that songs embedded deep in memory can ease pain and awaken these fading minds. Joy and life are resuscitated, and our cultural fears over aging are confronted. (Documentary)

Movies About Aging, Dying & Grief

3156 The Sixth Sense (PG-13, IMDb 8.1) A boy who communicates with the dead seeks the help of a disheartened child psychologist.

4557 Me and Earl and the Dying Girl (PG-13, IMDb 7.7) Greg is coasting through senior year of high school as anonymously as possible, avoiding social interactions like the plague while secretly making spirited, bizarre films with Earl, his only friend. But both his anonymity and friendship threaten to unravel when his mother forces him to befriend a classmate with leukemia.

2103 Coco (PG, IMDb 8.4) Despite his family’s baffling generations-old ban on music, Miguel dreams of becoming a musician. Desperate to prove his talent, Miguel finds himself in the stunning and colorful Land of the Dead following a mysterious chain of events. Along the way, he meets charming trickster Hector, and together, they set off on an extraordinary journey to unlock the real story behind Miguel’s family history. (Animated)

706 Young at Heart (PG, IMDb 7.9) Documents the true story of the final weeks of rehearsal for the Young at Heart Chorus in Northampton, MA, whose average age is 81, and many of whom must overcome health adversities to participate. Their music goes against the stereotype of their age group. Although they have toured Europe and sang for royalty, this account focuses on preparing new songs for a concert in their home town. (One of our favorite movies. Watch the preview then the movie.)

3463 The Bucket List (PG-13, IMDb 7.4) Billionaire Edward Cole and working class mechanic Carter Chambers are worlds apart. At a crossroads in their lives, they share a hospital room and discover they have two things in common: a desire to spend the time they have left doing everything they ever wanted to do and an unrealized need to come to terms with who they are. Together they embark on the road trip of a lifetime, becoming friends along the way and learning to live life to the fullest, with insight and humor.

3070 The Fault in our Stars (PG-13, IMDb 7.7) Hazel and Augustus are two teenagers who share an acerbic wit, a disdain for the conventional, and a love that sweeps them on a journey. Their relationship is all the more miraculous, given that Hazel’s other constant companion is an oxygen tank, Gus jokes about his prosthetic leg, and they meet and fall in love at a cancer support group. (Based on a wonderful book by John Green)

4375 Beetlejuice (PG, IMDb 7.5) Thanks to an untimely demise via drowning, a young couple ends up as poltergeists in their New England farmhouse, where they fail to meet the challenge of scaring away the insufferable new owners. In desperation, the recently dead newlyweds turn to an expert frightmeister, but he’s got a diabolical agenda of his own.

3737 Manchester by the Sea (R, IMDb 7.8) After his older brother passes away; Lee Chandler is forced to return home to care for his 16-year-old nephew. There he is compelled to deal with a tragic past that separated him from his family and the community where he was born and raised.

1059 P.S. I Love You (PG-13, IMDb 7.0) A young widow discovers that her late husband has left her 10 messages intended to help ease her pain and start a new life.

3838 Steel Magnolias (IMDb 7.3) This heart wrenching drama is about a beauty shop, in Louisiana owned by Truvy, and the tragedies of all of her clients.

4535 My Sister’s Keeper (PG-13, IMDb 7.4) Eleven your old Anna Fitzgerald seeks an attorney to earn medical emancipation from her mother who wants Anna to donate a kidney to her sister. When her older sister had leukemia Anna was conceived to become a bone marrow donor. She now realizes if her sister had not been sick, she would never have been born.

3686 The Things We Lost in the Fire (R, IMDb 7.2) A recent widow invites her husband’s troubled best friend to live with her and her two children. As he gradually turns his life around, he helps the family cope and confront their loss.

2731 Death at a Funeral (R, IMDb 7.4) A myriad of outrageous calamities befall an eccentric English clan with more than a few skeletons in its closets, when its patriarch dies an unexpected death. Soon, every complication imaginable befalls the grief-stricken mourners.

2 What Dreams May Come (PG-13, IMDb 7.1) Chris Neilson dies to find himself in a heaven more amazing than he could have ever dreamed of. There is one thing missing: his wife. After he dies, his wife, Annie killed herself and went to hell. Chris decides to risk eternity in hades for the small chance that he will be able to bring her back to heaven.

If someone had a length of old clothes line rope, we jumped rope until we were bored. With the appearance of a pink rubber ball, we’d move to the wall by the stairs of the apartments at the end of the block, and when that got boring, we’d attach roller skates to our Buster Brown shoes and race around the block on wheels wearing the skate key on a shoelace around our necks. Around lunch time all of the neighborhood kids would disappear into their houses for lunch and reappear later to regroup and find new things to keep us occupied.

If someone had a length of old clothes line rope, we jumped rope until we were bored. With the appearance of a pink rubber ball, we’d move to the wall by the stairs of the apartments at the end of the block, and when that got boring, we’d attach roller skates to our Buster Brown shoes and race around the block on wheels wearing the skate key on a shoelace around our necks. Around lunch time all of the neighborhood kids would disappear into their houses for lunch and reappear later to regroup and find new things to keep us occupied. Hot, sweaty, and sticky, we’d continue to play as the afternoon faded into early evening, and as fathers began returning home from work, we’d hear our names called out and one by one our play group got smaller and smaller. Even those kids whose names weren’t called, would reluctantly head for home until the streets were once again empty.

Hot, sweaty, and sticky, we’d continue to play as the afternoon faded into early evening, and as fathers began returning home from work, we’d hear our names called out and one by one our play group got smaller and smaller. Even those kids whose names weren’t called, would reluctantly head for home until the streets were once again empty. I watched my mother spend the day at her treadle sewing machine and I can still hear the cluck, cluck, cluck of it if I imagine hard enough. Our woolen floor rugs spent the summer in our basement and on the floor was a coarse, textured covering that took nearly all summer for the bottoms of our bare feet to get used to the roughness. How clearly I remember that.

I watched my mother spend the day at her treadle sewing machine and I can still hear the cluck, cluck, cluck of it if I imagine hard enough. Our woolen floor rugs spent the summer in our basement and on the floor was a coarse, textured covering that took nearly all summer for the bottoms of our bare feet to get used to the roughness. How clearly I remember that. Dessert for dinner! What an amazing meal to have during a heat wave.

Dessert for dinner! What an amazing meal to have during a heat wave.

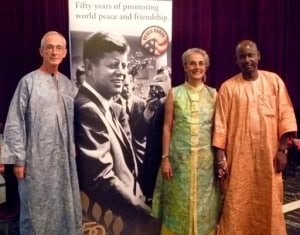

period of time in Mali, they were very different in scope and style and subject matter. Asifa’s job became an effort to train the Malians to grow Moringa, a miracle tree whose leaves cure whatever it is that ails you including malnutrition and arthritis. This was to be done, as Asifa says, all in a simplified Bambara. And David’s task was to help promote and improve a radio station 20 minutes away by bicycle, speaking French (which David had learned long ago but hardly remembered).

period of time in Mali, they were very different in scope and style and subject matter. Asifa’s job became an effort to train the Malians to grow Moringa, a miracle tree whose leaves cure whatever it is that ails you including malnutrition and arthritis. This was to be done, as Asifa says, all in a simplified Bambara. And David’s task was to help promote and improve a radio station 20 minutes away by bicycle, speaking French (which David had learned long ago but hardly remembered).