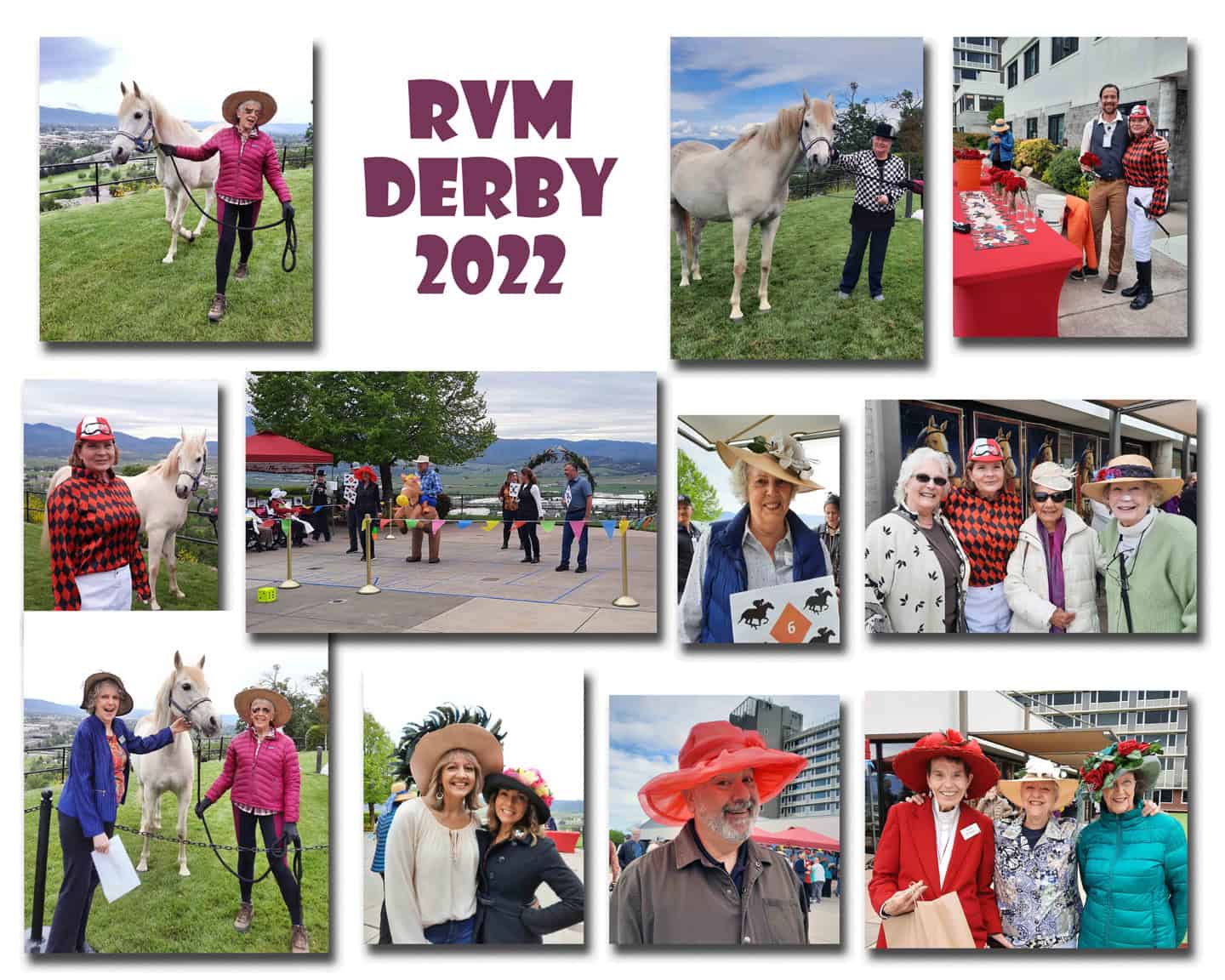

Posted in A&I

August in the Library

by Anne Newins

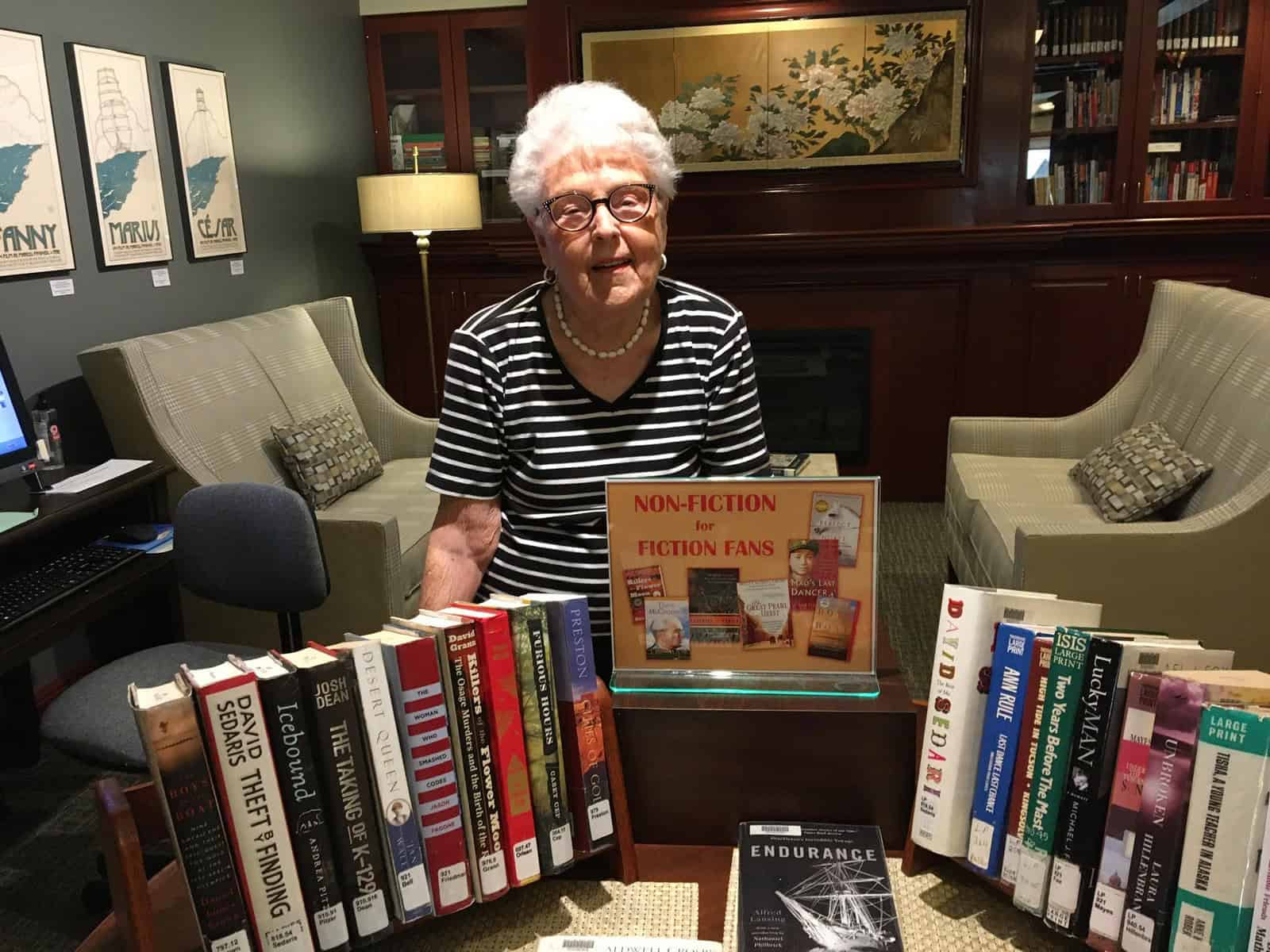

Several months ago, resident Janice Williams inquired about creating a bibliography for the library’s display table. Janice is a retired librarian and enjoys non-fiction. She told me that “more people would check out non-fiction books if they read like fiction.” Janice then offered to create a list of non-fiction books that she believes would appeal to fiction fans.

Janice is right about the wide disparity in readership between the two types of books. She also is correct in her belief that many readers want interesting characters and events and may not want an excess of details. The books chosen for the display meet those criteria.

Kudos to Janice for her expertise and assistance. She is pictured above next to the display. She has selected numerous volumes that may interest you, covering a wide range of subjects. Below are a few sample topics and book titles:

True Crime:

The Great Pearl Heist, by Molly Crosby

Murder of Innocence, by James Patterson

Last Dance, Last Chance, by Ann Rule

World War II:

A Woman of No Importance, by Sonia Purnell

Unbroken, by Laura Hillenbrand

Adventure and Exploration:

Endurance, by Alfred Lansing

Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver, by Jill Heinerth

Desert Queen, by Janet Wallace

River of Doubt, by Candice Millard

Outstanding Authors:

Theft by Finding, by David Sedaris

At Home, by Bill Bryson

Hillbilly Elegy, by J. D. Vance

NIT WIT NEWZ — August 2022

(Nit Wit Newz is an unauthorized, often unreliable, on-line source of misinformation designed to keep Manor residents abreast of the inconsequential, trifling, and superficial events that dramatically shape and inform our everyday lives here at Rogue Valley Manor).

WINGS OVER MEDFORD

J. Byrd Holmes, CEO of Home Tweet Home, south Medford’s largest birdhouse retailer, recently sent Nit Wit Newz this letter:

Dear Nit Wit Newz:

We share an urgent problem. In the wake of last month’s freak July 2 storm, severe damage swept through our avian community here in south Medford, and, most particularly, Rogue Valley Manor.

Devastation among your campus bird housing was widespread.

Hanging homes were blown from trees, roofs were lost; still other homes became dislodged from seemingly secure posts and rafters. Worse, we can assume the near-complete loss of all open-nest bird sanctuaries to the fury of that wanton, early summer tempest.

With another capricious, climate-changing winter lying ahead, a dire homeless crisis looms. It is not too early to provide adequate weather protection for our neighborhood winged-friends.

Keenly aware of Nit Wit Newz’s vast reach and powerful influence among RVM residents, we here at Home Tweet Home would like to enlist your help by alerting RVM readers to this important announcement:

HOME TWEET HOME’S NEW 2022-23 LINE OF LUXURY BIRD HOUSING IS NOW AVALIABLE!

Our new models include these stunning new features:

-Solar Paneled Roofs. Not only do these roofs keep the entire family cozy in the chilliest of evenings, but—for those moms-to-be—that extra warmth, ornithologists tell us, could shorten the incubation period, meaning less time sitting on those uncomfortable, lumpy eggs for days on end.

-All of our new models have eliminated those stubby pegs sticking out of the front entrance limiting only a single bird to stand or land on at any one time. Replacing those homely pegs are fulsome, wrap-around porches. These porches provide ample take-off and landing space for those maiden test flights by the newly-hatched. Moreover, these expansive landing areas will prove helpful to senior family members whose eyesight and wing-to-foot coordination might be waning.

– New this year, for those extended families sharing a single home, say goodbye to cramped, close quarters; two and three-bedroom units are now available. These multi-chambered homes also provide space for out of town guests and offer superb time-share and Airbnb income opportunities, although, unlike we mortals, it does not appear that the aviary-world has yet devolved into monetizing their living quarters.

-A house, of course, is not a home without furnishings. No need for your new occupants to scavenge about the neighborhood. Home Tweet Home has a warehouse filled with a wide variety of twigs, leaves, sticks and tiny braches that will suit the decorating tastes and comfort demands of all of your new chirping dwellers.

But wait—there’s more!

Order your new house today at www.hometweethome.com using promotion code: S.O.B. (that’s, Save Our Birds), and we’ll include a free, illuminated, roof-top “Vacancy/No Vacancy” sign with every house purchase. These signs are designed to end unpleasant occupancy-rights squabbles among our fine feathered friends before they start.

A special discount is available to birdhouse customers that plan to house carrier pigeons that have previously served delivering vital military messages in the armed forces. It’s our way of saying “Thank you for your service.”

Cash strapped? Worry not. Feathered Housing Administration (FHA) loans are available.

Let’s fight this homeless crisis together! Check out our www.hometweethome.com website today.

Keep ‘em flyin’!

- Byrd Holmes

A FULL DISCLOSURE NOTE TO OUR READERS: Nit Wit Newz prides itself in adhering to the highest journalistic standards. That includes, of course, maintaining a sharp delineation between editorial content and commercial advertising.

Some of our readers may find Mr. Holmes’s letter—appearing in space traditionally reserved exclusively for editorial copy—to be offensively commercial (i.e., selling of birdhouses). Indeed, the letter gave pause to Nit Wit Newz’s Board of Directors as well. Faced with the dilemma of running this clearly, self-serving, promotional letter or, instead, maintaining our code of reportorial principles, caused ethical angst among board members. This concern was short lived. Those pesky integrity issues were quickly jettisoned when Home Tweet Home offered the generous, “carrier pigeon” discount on Nit Wit Newz’s purchase of the birdhouse that now graces the rooftop of NWN’s headquarters.

—A. Looney

THE ROCKS OF NAPO’OPO’O

by Leilani Lewis (Spring 1991)

(submitted by Madge Walls)

It’s Friday morning. Time to leave my cares and responsibilities behind in Honolulu and fly to Kona for the weekend. I have three days to putter around my yet-to-be-finished house on Napo’opo’o Road, plant ground cover on the slopes above the house, and develop a site plan for steps and pathways all over the sloping land, connecting one level with the next, using rocks – the flatter the better – that I’ve been collecting from around the property.

Mid-Friday afternoon: hot and sweaty I feel like going for a swim in Kealakekua Bay. It’s just a two-mile drive down the road. Five minutes later I’m walking onto the black sand beach – having just experienced that familiar feeling I always get when I walk from the gravel parking area, past the heiau on the right and the lava rock wall and bay on the left, towards the beach area – that feeling sensation of having passed from ordinary everyday reality into a magical timeless realm. Kealakekua Bay and its clear pristine waters, the pali above, the Captain Cook monument at the far end of the bay, black sand Napo’opo’o Beach and its rocky shore, the tree-shaded grassy area between the heiau and the beach: this whole scene is a place of blessing for me – where time stands still, then disappears – a place where all my worries and concerns literally wash from me as I lazily swim in the bay and lie in the sun.

As I walk onto the beach I notice for the first time how many smooth black rocks there are. They’d make wonderful stepping stones on my land. They’re so flat – so perfect for making steps and pathways. I drop my towel and rubber slippers on the sand and start walking all over the rocky area past the beach – now and then stooping down to run my hands over the smooth surface of the rocks.

There’s a small circular sandy spot about six feet in diameter amidst all the rocks, and I find myself picking up round flat rocks and placing them in a circle within the sandy area. The pile has grown to about fifteen stepping-stone rocks when I am gently pulled out of my rock-collecting reverie by the sound of a voice inside: “Leilani, remember what you’ve been taught. When you want to take from Nature, first ask Nature’s permission” “Yes, of course.” So I sit down on the edge of the circle of rocks and .silently speak to the largest rock in the center.

“Big Rock, may I take all of you rocks that I’ve collected today and use you as stepping stones on my land near here?”

“No.”

“No?! What do you mean, no? Are you sure? Why not?”

“Because we belong here. This is our home.”

“But you’re going to be used for a good cause. I mean, you’ll be used as stepping stones along pathways connecting different areas of my property.”

“No, Leilani. We belong here by the bay. Our only function is to be here and lie in the sun and tumble in the surf at high tide. We simply are – with no other purpose.”

“Okay, I’m getting the picture. I’m disappointed, but I won’t argue with you. I know you speak wisely. I’ll honor your message. Your words are unexpected, but I obviously need to learn this lesson.”

I leave the circle of rocks and go for a swim along the shore – feeling light and happy as the waves gently tumble me around and wash over me. Later, as I’m lying in the sun I hear Rock speak again.

“Leilani, go ahead and pick out a small black rock and take it with you to your home site up the road. Put it prominently somewhere as a reminder of this teaching today.”

“Okay. Thank you. That’s a wonderful idea.”

I pick out a little black rock – smooth, flat, and round – and take it with me when I return to the land a while later. After rinsing off the sand I put it in the garage, knowing I’ll find a special place in the house for it later.

That evening I visit Mary Helen, who lives on the slopes of Hualalai above Kailua. We’ve been good friends since preschool days and we know each other well. I tell her about my conversation with the rocks. She says she heard recently that the State Government is planning to bulldoze the rocks away at Kealakekua Bay and even encourages their removal by anyone and everyone – so that the sandy part of the shore can be extended into the now rocky area.

Hearing this news I’m excited about returning to Napo’opo’o Beach the next day to converse with the rocks again – this time telling them about the bulldozers – and see if that makes any difference to them.

Early the next morning I return to the beach and immediately head towards the circle of rocks. Gone! All the rocks I’d collected and placed in a circle are now gone. I turn to the surrounding rocks along the shore and whispered out loud to them, “What happened? Where’d they all go? Who removed them?”

The rocks reply, “It doesn’t matter how they were removed. What matters is those rocks belong here along the shore with us – not in your circle of so-called stepping stones.”

I press on with more questions now that I have the bulldozing information to present to them. I tell them what Mary Helen said.

“Now may I take some of you rocks up the hill to use as stepping stones on my land? I mean, you’ll be removed anyway by the bulldozers.”

“That doesn’t matter. The answer is still no. Just because the Government people say that rocks will be removed from this beach doesn’t mean it is right to do so. You know better. Stick to what you know – not what everyone thinks. This too is a lesson you still need to learn.”

“Okay, Rock, one last question. Why do you say no to me now when members of the Rock family have always said yes before? I have a few special rocks that I’ve taken home with me from various places – always with the rock’s permission.”

“We’ve already told you. Lately, you’ve become too focused on the function of rocks instead of simply appreciating us as we are. When you return here tomorrow, just come and enjoy. No questions. Just be here. Like us.”

“Hmmnn…okay. Thank you. See you tomorrow.”

Sunday morning as the sun rises over Mauna Loa I return to the beach. In the early morning light I hop around among the rocks, smiling. A few of them are now back in the circular area. I start to wonder out loud and then decide to just let the mystery be.

“Don’t worry. I won’t even ask.”

As I walk past my rock friends towards the gentle morning surf, my eyes begin to water. I feel a deep sense of belonging.

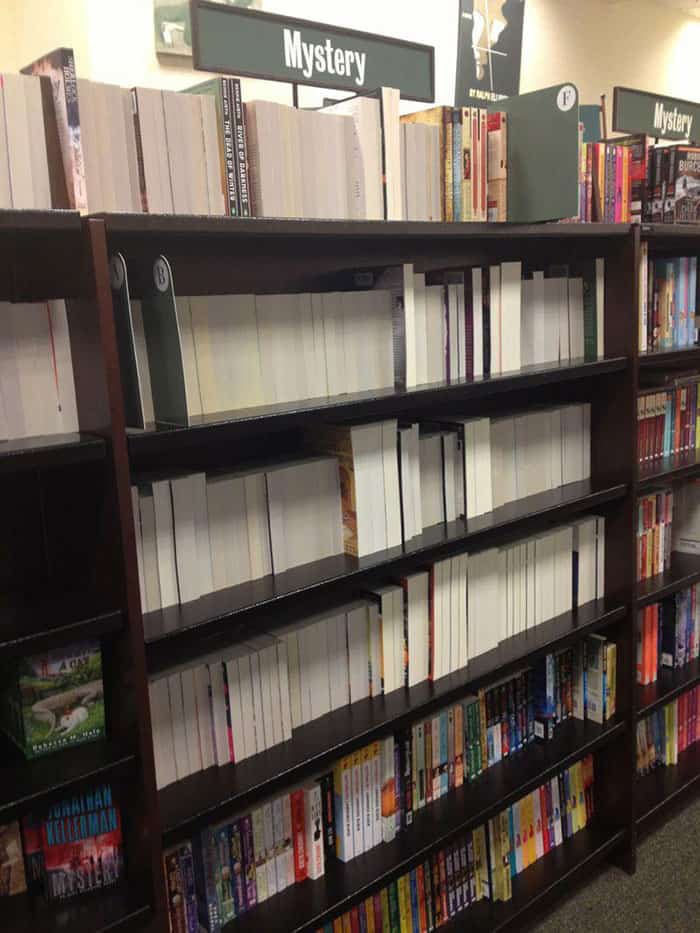

July in the Library: THE SEQUEL!

by Anne Newins

The June display of prolific and famous authors is proving popular and is going to carry over into July. This display will continue to highlight authors who have been enjoyed nationally and at RVM. It will include more writers such as Debbie Macomber, Randy Wayne White, Charles Todd, Martin Walker, Dale Brown, and Dorothea Frank. They write in differing genres including romance, family dramas, thrillers, and mysteries.

Book Review: The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot

by Bonnie Tollefson

Book Review – The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot, Marianne Cronin, Harper Collins Publishers, 2021.

Bonnie Tollefson

I stopped by the RVM library the other day to check out a book for my quarterly book review. I try not to browse there too often because I end up with way too many books I want to read, but I was looking for a book that would say something different to everyone like Phone Booth at the End of the World or a book that would teach us something like the one about Fish Owls. I went home with the first in Janet Evanovich’s new series, Recovery Agent and Snowblind a debut novel by Ragnar Jonasson. I got home and returned to reading The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot which I had checked out of the Jackson County Public Library. Have you ever had a book reach out and grab you by the neck and not let go? Meet Lenni and Margot in The One Hundred Years of Lennie and Margot.

Lenni is 17 years old and has a “life-limiting condition” the current trendy term for terminal. Margot is 83, and has a heart condition. They are going to do surgery but the prognosis is not good. They both live at the Glasgow Princess Royal Hospital. Between Margot and Lenni they have lived 100 years. Lenni is funny, precocious, and curious. Margot is feisty, fruitcake eating, and a rebel. After meeting the hospital chaplain Lenni comes up with a marketing campaign to increase usage of the chapel while Margot almost ends up in the trash cart after a letter is accidentally thrown away. Lenni manages to join the over 80 class in the art room and meets Margot. They decide to paint a picture representing each year of their 100. As well as painting, they each share the stories of their lives. The reader learns about Lenni’s life in Sweden before moving to Glasgow and her dysfunctional family. Margot shares stories of her first husband who left her, her baby son who died of a heart defect, and her second husband who got Alzheimers. The book is about friendship no matter the age, love in all forms, and the desire to leave a mark on the world. Yes, the ending is sad (having a box of tissues handy would not be remiss) but it is uplifting as well. Lenni learns that death may not be as scary as she was afraid it was.

not good. They both live at the Glasgow Princess Royal Hospital. Between Margot and Lenni they have lived 100 years. Lenni is funny, precocious, and curious. Margot is feisty, fruitcake eating, and a rebel. After meeting the hospital chaplain Lenni comes up with a marketing campaign to increase usage of the chapel while Margot almost ends up in the trash cart after a letter is accidentally thrown away. Lenni manages to join the over 80 class in the art room and meets Margot. They decide to paint a picture representing each year of their 100. As well as painting, they each share the stories of their lives. The reader learns about Lenni’s life in Sweden before moving to Glasgow and her dysfunctional family. Margot shares stories of her first husband who left her, her baby son who died of a heart defect, and her second husband who got Alzheimers. The book is about friendship no matter the age, love in all forms, and the desire to leave a mark on the world. Yes, the ending is sad (having a box of tissues handy would not be remiss) but it is uplifting as well. Lenni learns that death may not be as scary as she was afraid it was.

This book is Marianne Cronin’s debut novel and took her seven years to write. I hope we don’t have to wait another seven years for her next offering. Although I checked this book out from the public library, you can too. The shopping bus goes there every Wednesday and library cards are easy to get. Maybe next quarter you will get a review of either Recovery Agent or Snowblind.

Language Fun

Contronyms

by Connie Kent

Contronyms are words that have two contradictory meanings. Did you know there was such a thing? Here are a few. They are rare.

1. apology – a statement of contrition for an action, or a defense of one

2. bolt – to secure, or to flee

3. bound – heading to a destination, or restrained from movement

4. cleave – to adhere, or to separate

5. dust – to add fine particles, or to remove them

6. fast – quick, or made stable

7. left – remained, or departed

8. peer – a person of nobility, or an equal

9. sanction – to approve, or to boycott

10. weather – to withstand, or to wear away

Nit Wit Newz — June 2022

(Nit Wit Newz is an unauthorized, often unreliable, on-line news source designed to keep Manor residents abreast of the inconsequential, trifling, and superficial events that dramatically shape and inform our everyday lives here at Rogue Valley Manor.

PEOPLE MOVING BEHEMOUTH EYES EXPANSION

Seeking to increase share of Medford passenger-transport market, giant firm, Uber, targets small private taxi outfit for takeover.

Makes self-described “generous offer” to Rogue Valley Manor for intra-campus taxi service, Manor Express.

No luck. RVM management spurns Uber buy-out bid.

Cites resident’s fondness for Manor Express (ME) service. Unwilling to forgo beloved, prompt, and free campus transportation service for unknown, outside firm. Moreover, cherish long-standing relationships with super-friendly, always prompt, skilled Manor Express drivers. Asked about the ME, one rider says, “It’s like having a dozen or so of your own private chauffeurs at your dialing fingertips.” Asked about Uber, another says, “Why pay to get into a car with a stranger?”

“Reasons enough—Manor Express not for sale!” exclaims RVM management.

Uber executives angered by turndown of “generous offer.” Proceed to hammer out hostile takeover strategy: 1). Marshal all area Uber vehicles. 2). Swarm RVM site with Uber taxis—station one at every corner). 3) Tap phone lines. Intercept #7433 phone calls and beat Manor Express cabs to resident cottages. Convinced residents will sensibly prefer Uber service.

Outside observers fear Manor Express doomed—outmanned, out-vehicled. Give soon-to-be embattled defenders of RVM taxi service scant day or two before collapse under weight of formidable Uber forces.

Uber management makes final demand for Manor Express capitulation before initiating aggressive takeover plan.

Cheeky ME defenders reply: “Go jump in the lake!”

Uber negotiators puzzled. Decide “jump in lake” may not be a good faith counter-offer. Proceed with aggressive takeover strategy.

Unbeknownst to Uber, takeover strategy details leaked to ME drivers.

Nimble Manor Express drivers quickly craft counter-strategy: 1). Alert residents to only accept rides in cabs with dashboard green light. 2). Share ME rides with as many fellow residents as possible during attempted siege. 3). Encourage car-owning residents to offer neighbors rides to destinations. 4). Walk to destination, if at all possible.

Residents eagerly comply with Manor Express counter-strategy. “If you don’t see green, you’re in the wrong machine” becomes chant of ME riders.

Mobilization of massive Uber fleet begins. Manor streets smothered by near bumper-to-bumper coverage of campus.

Reality bites. Uber drivers dumbstruck to find ‘though arriving first for pick-ups, Manorites shun Uber rides. Await ME autos instead. Happily pile in along with three, sometimes four, other ride-seeking neighbors.

Uber cars remain passenger-less. Attempt to monetize takeover of ME slips away.

Resolve of fare-starved Uber drivers wanes. Promise of new source of income stream from RVM denizens dissolves.

Predicted “day or two” conflict proves correct. But it’s frazzled Uber giant that crumbles not flinty, indomitable Manor residents and “Green Light Express” drivers.

One-by-one, Uber vehicles slink out of RVM campus streets.

Events serve as a reminder: A tiny band of gritty, committed citizens can thwart the designs of an uninvited aggressor— anywhere.

A celebratory parade of Manor residents waving yellow and blue banners re-takes Rogue Valley Manor streets.

—A. Looney

Reunion Planning

by Tom Conger

Reunions—at this stage in our lives, almost all of us have been there: high school reunions, college reunions, church reunions, summer camp reunions, family reunions, military unit reunions, you name it. A few lucky souls have even been tapped to organize our reunions—sometimes more than once. Those born and raised in what is now the Peoples Republic of Hawaii have it even more enviably: we get to [try and] plan a reunion from long distance, spanning thousands of miles of open ocean plus attendant time zone differentials.

In planning, say, a high school quinquennial, you should first attempt to cobble together some semblance of a committee—a cadre of loyal comrades [allegedly] willing to assist in handling the myriad details. Mind you, once past your silver anniversary, most all the willing/capable classmates have either burned out, lost interest entirely, or died. Thus you begin with a ragtag roster of revelers who may not even be friendly with half the other committee members. And from those humble beginnings you attempt to produce a schedule of events attractive enough to draw your widespread constituency to the fair [distant, and very costly] isles to press flesh with residents wealthy enough to retire in one of the most expensive communities on the planet.

Having gathered your forces, now formulate an agenda. A reconnection calendar usually runs like this: kick-off gathering for drinks & dinner; some activities based on shared interests (museum tours, sunset sails, etc.); memorial service to recognize the burgeoning list of class decedents; an annual school-wide event (Alumni Luau?); a farewell picnic. This formula works pretty well up through your 50th reunion. After that major milestone, things deteriorate pretty rapidly.

By our 60th reunion in ‘17, we had exhausted all manpower resources—nobody was willing to step forth and lead—so they craftily conscripted the undersigned, exiled to the left coast in order to afford retirement. Leadership from the mainland is sketchy, but classmates went deaf whenever I pled my case. Plus, they said, the school now had staff specifically assigned full-time to reunion coordination, and “Everything’s Gonna Be All Right.”

In the end I was proven right: successful oversight simply cannot be done from three thousand miles away, and some functions delegated to volunteer “leaders” were never done properly, if at all. Thus, Doug, my on-island angel and I swore after the farewell picnic to never again be involved in reunion planning—the old Roberto Duran approach: “¡No mas!”

Comes the 65th. Now the majority of classmates are truly debilitated, disinterested, or dead. But that ol’ five-year latch-up rolled around, sure as Father Time totes an hourglass. And the school’s Alumni Relations Dept came a-calling… moi. Please bear in mind that in late 2021 the world was still beset by the Covid-19 pandemic, Hawaii was closed to outside travel, and the Guv’s office was emitting directives, almost weekly, regarding new restrictions on gatherings in the Peoples Republic. And most of our octogenarian classmates were looking more toward their celestial exit than meeting their classmates clad in full PPE.

A questionnaire, distributed to all 222 classmates, polling interest in reunion activities, garnered a whopping 16 responses—7 of them negative. But the school had already been forced to cancel two prior years’ reunions (big money raisers!), and was determined to pull one off this year—deadly contagious infections be damned. So Doug & I plowed forward. By sheer love of school we were able to rope in the former Trustee Chair plus the wife of another Chairman Emeritus, thus the “committee” was fleshed out—in skeletal fashion.

No matter your agenda, when overarching conditions are completely reliant on relaxation of quarantine edicts from a clueless State government, all planning involves fallback alternatives for each event. In sum, ya gotta plan two entire reunions—one that folks want, and another that authorities might allow. Given the scant response to our survey, we initiated planning on a downsized basis. The ritual cocktail evening was out to begin with, as too few classmates were willing or able to drive after dark. So we focused on a nice luncheon somewhere. But where? There were too few commercial venues still operating, given social distancing strictures, and the on which met most of our criteria could not accommodate us on the day we had chosen. So we ended up prevailing on a classmate’s membership at the world-renowned Outrigger Canoe Club, whose main dining room had not yet reopened for general use due to lockdown orders—our special session was a good opportunity to utilize a facility which needed the practice, and the revenue. But should a Covid-19 spike suddenly recur, we needed a fallback. We chose the private home of a classmate for a potluck affair; he could handle a crowd our size, and everybody could bring a take-out dish from whatever bistro they favored—should it still be serving in the pandemic . . .

The school staged activities throughout Alumni Week, and we included some in our overall agenda. As there were no plausible alternatives, we were unable to offer fallback events should the school be forced to cancel. One school-sponsored function was the mid-week Kupuna Lu’au (“old-folks’ feast”), for reunion classes 65th and above; obviously, ranks of alumni who had started kindergarten before/during WWII were rather thin, so the event could be held at the President’s home. Should an order come from the state Capitol demanding social-distancing, we could revert to the school cafeteria—a considerable drop in opulence/cachet, and attendance…

We put forth mailers and digital notices promoting the June reunion, and waited for classmates to register. Don’t forget: our constituency is into our 80s—with attendant aches, pains, and timorousness—75% of whom no longer live in the isles. Response was slow. So slow, in fact, that this mainland resident was ready to cancel the whole damting. But school officials were more patient, tenacious, and anticipative of a restorative shot in the contributions arm.

With a month to go, we still had only about 30 people signed up for the reconnections luncheon, the one true class event, and prospects were grim. That’s when the on-island sector of the committee formed a SWAT team to make personal calls and roust out lethargic (eccentric?) Oahu classmates who’d just not gotten around to signing up (or were simply confused).We eventually strong-armed a group of 60—alumni, spouses, widows, care-givers, special guests, and others – to convene at the foot of Mt. Leahi for a brief interlude of camaraderie, nostalgia, and good cuisine.

The roll of 137 decedents was printed and laid at each place-setting, and our very first male teacher in elementary school, now 97 years old, shared some poignant memories of our class history from the perspective of a rookie teacher coming to a distant territory soon after the end of a world war. It was lovely. We felt sorry for those who chose not to join us. And we’re giving thought to not inviting them next time . . .

Next time…? I think: ¡No Mas!