Ranked-Choice Voting: A Viewpoints Feature

By Robert Mumby

The Complement, Viewpoints, and their contents are not supported or endorsed by, or representative of, the RVM administration or the Residents Council. Opinions expressed are those of the author(s). Discussion is encouraged, either by the ‘’Reply” function at the end of every article, or by submitted letters or articles, which are subject to review and editing.

In this year’s election, there is a proposed amendment to the Oregon Constitution to adopt ranked-choice voting: Measure 117. This article presents an overview and summary of the measure. For the complete text, pro and con arguments, history and background go to the Ballotpedia webpage for Oregon Measure 117

What is ranked-choice voting?

Known as “instant-runoff voting,” this method was invented around 1870 and has been adopted by a few democracies worldwide. Australia has used ranked-choice voting in its lower house elections since 1918. This system allows voters to rank candidates by preference, ensuring a winner who most satisfies the majority.

Here’s how it works. In ranked-choice voting elections, voters can—but do not have to—rank the candidates in order of preference. If a candidate wins a majority of first-preference votes, they win. If not, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is eliminated, and the second-choice votes of those who preferred the eliminated candidate are reallocated to those still in the race. This process continues until one candidate achieves a majority.

Currently, Oregon voters who belong to a political party vote twice: during party primaries and in the final election. Non-party members in 10 states (including Oregon) cannot vote in the partisan primary. Other states have partially open partisan primaries.

Ultimately, Oregon voters choose between two or more partisan candidates. Besides Democrats and Republicans, there are seven recognized parties. This can cause a majority of citizens to vote for losing candidates and a winner who lacks widespread approval.

Ranked-choice voting could ensure that a winner has the approval of a majority by considering all preferences, not just the first choice. This mitigates the problem of winning by a mere plurality and ensures that public servants reflect the electorate’s true desires. It could also streamline the election process, making it less expensive and more efficient. Primaries and runoffs are costly, and critics argue that elections would improve if voters ranked their choices instead of voting twice and often for a party primary winner they don’t particularly support.

Instead of holding primaries, political parties would list all eligible candidates on a single final ballot, allowing a true consensus choice to emerge. Instant-runoff voting would eliminate the need for runoffs in close elections, say supporters of ranked-choice voting.

Do We Want Ranked Voting?

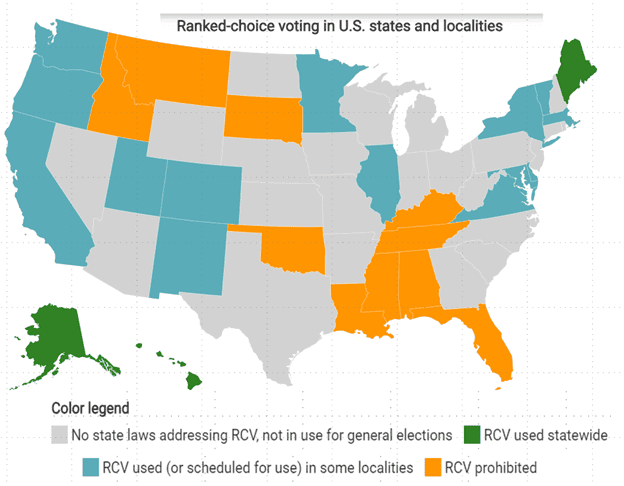

The system is used statewide in Maine (starting in 2020), by Alaska and Hawaii (starting in 2022), is pending in Nevada, and is used by municipalities and in other local elections in fourteen other states. Its use is prohibited in five states, and it has not been the subject of any legislation in 34 others. In Oregon, it is used in Benton County, Multnomah County, and Portland. The map below , from Ballotpedia, illustrates its use in the U.S.

Proponents argue ranked-choice voting ensures a majority winner and reduces spoiler effects from third-party candidates. Political parties are not significantly affected; they will still select and campaign for candidates. If two or more party members run for one office, then the ranking process gives more party members a voice in the selection than would be the case in which a single candidate is selected by a plurality.

In our current primary system, independent voters cannot vote in the party primaries—they have no chance to vote in the “first round” and have fewer choices on the final ballot. In the ranked choice system, all voters could participate, and voters would rank only those candidates they find acceptable. If all of their preferred candidates are eliminated before the final round, the result is no different from voting for a losing candidate under the present system.

Ballot Measure 117 would establish ranked-choice voting for federal and state elections, including president, U.S. senator, U.S. representative, governor, secretary of state, attorney general, state treasurer, and commissioner of labor and industries. However, it allows but does not require ranked-choice voting by counties, cities, and other local jurisdictions. This means a voter may find that some officials are elected either the current way by party primary, or through ranked-choice voting. This could cause confusion because for multi-candidate non-partisan positions, you currently vote for only one candidate, but if it’s a ranked-choice position, you rank all acceptable candidates in order of preference. The ballot should clarify the voting method for each position. Nevertheless, one might question why the amendment permits local governments to choose their voting method.

Representative Pam Marsh, a sponsor of the ballot measure, explained: “We explicitly gave local jurisdictions the opportunity to use ranked-choice voting because we thought it was helpful for clarity. We know some jurisdictions will want to jump in, while others will stick with the current system. Adapting to ranked-choice voting will require voter education and community discussion, and not all places will want to take that on.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!